One of the troublesome things that has come up in the Amazing Zoo Synod in Rome over the past couple of weeks is the tired, foolish nonsense of ordaining women. Or, as they couch it, “considering” or “examining” or “reflecting on” the possibility of ordaining women.

Stupidissimus. The issue is closed. Pope John Paul II addressed it, and by his declaration settled it for all time. You can’t remain Catholic when you bring back for debate a question that has been definitively settled by the Church, settled at the highest level of authority precisely and expressly to remove all doubt.

When did JPII do this? In 1994, in the papal Apostolic Letter “Ordinatio Sacerdotalis” (hereafter, “OS”). He said:

Wherefore, in order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter of great importance, a matter which pertains to the Church's divine constitution itself, in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren (cf. Lk 22:32), I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful.

Now, at the time, some people took this to constitute an ex cathedra statement, an intentionally infallible definition of Catholic doctrine, which (because it is infallible) cannot be reversed. Ex cathedra statements by the pope are understood to be a subset of the class of extraordinary acts of the magisterial office of the Church, such extraordinary exercises being infallible from their authoritative source, and manifested their own expression of definitude. (They are distinguished from ordinary acts of teaching by the bishops who exercise the magisterial office of the Church, which can be infallible, but are not always infallible.) About a year later, however, Cardinal Ratzinger (then the Prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, CDF), seemingly said it was not ex cathedra. Or rather, what he said is:

founded on the written Word of God, and constantly held and applied in the Tradition of the Church, it has been set forth infallibly by the ordinary universal Magisterium (cf. Lumen Gentium, 25). Thus, the Reply specifies that this doctrine belongs to the deposit of the faith of the Church. It should be emphasized that the definitive and infallible nature of this teaching of the Church did not arise with the publication of the Letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis. In the Letter, as the Reply of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith also explains, the Roman Pontiff, having taken account of present circumstances, has confirmed the same teaching by a formal declaration, giving expression once again to quod semper, quod ubique et quod ab omnibus tenendum est, utpote ad fidei depositum pertinens. In this case, an act of the ordinary Papal Magisterium, in itself not infallible, witnesses to the infallibility of the teaching of a doctrine already possessed by the Church.

That was in a 1995 Explanation (“Ex”) by CDF of a 1995 Responsum ad Dubium (“RaD”) regarding whether the declaration of OS was definitive and was part of the deposit of faith. The response itself was affirmative:

This teaching requires definitive assent, since, founded on the written Word of God, and from the beginning constantly preserved and applied in the Tradition of the Church, it has been set forth infallibly by the ordinary and universal Magisterium (cf. Second Vatican Council, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium 25, 2). Thus, in the present circumstances, the Roman Pontiff, exercising his proper office of confirming the brethren (cf. Lk 22:32), has handed on this same teaching by a formal declaration, explicitly stating what is to be held always, everywhere, and by all, as belonging to the deposit of the faith.

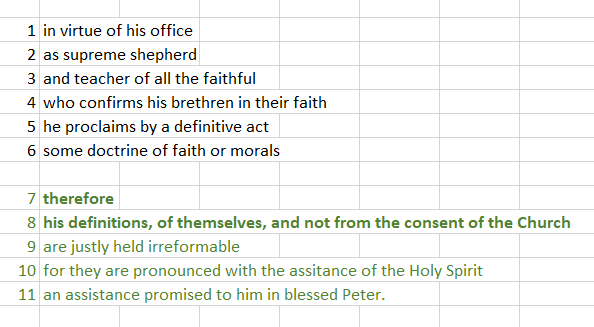

Whether the original declaration in OS was an ex cathedra teaching, can, however, be addressed from prior principles and teachings, and (for the intervening year before CDF issued RaD and Ex) could only be addressed by those methods. Indeed, prior teaching already gives us criteria by which to recognize an ex cathedra teaching by the Pope. In 1870, Vatican I, in its Dogmatic Constitution Pastor Aeternus (PA), distinguished so:

And this is the infallibility which the Roman Pontiff, the head of the college of bishops, enjoys in virtue of his office, when, as the supreme shepherd and teacher of all the faithful, who confirms his brethren in their faith (Luke 22:32), he proclaims by a definitive act some doctrine of faith or morals. Therefore his definitions, of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church, are justly held irreformable, for they are pronounced with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, an assistance promised to him in blessed Peter.”

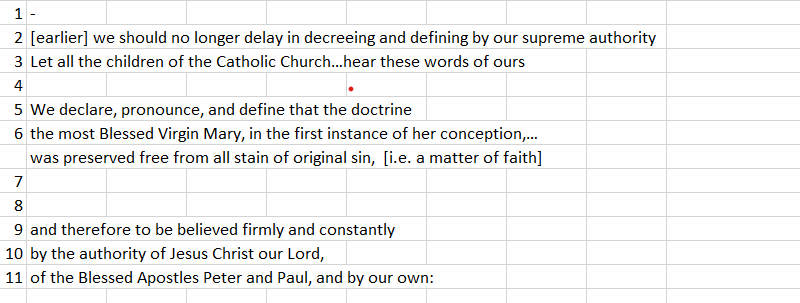

Now, virtually all Catholic authors and authorities agree that there have been (at least) two instances in which the pope issued an ex cathedra teaching. The first was by Pope Pius IX in his declaration that Mary was conceived immaculately, without original sin, in Ineffabilis Deus, (ID)

Wherefore, in humility and fasting, we unceasingly offered our private prayers as well as the public prayers of the Church to God the Father through his Son, that he would deign to direct and strengthen our mind by the power of the Holy Spirit. In like manner did we implore the help of the entire heavenly host as we ardently invoked the Paraclete. Accordingly, by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, for the honor of the Holy and undivided Trinity, for the glory and adornment of the Virgin Mother of God, for the exaltation of the Catholic Faith, and for the furtherance of the Catholic religion, by the authority of Jesus Christ our Lord, of the Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and by our own: “We declare, pronounce, and define that the doctrine which holds that the most Blessed Virgin Mary, in the first instance of her conception, by a singular grace and privilege granted by Almighty God, in view of the merits of Jesus Christ, the Savior of the human race, was preserved free from all stain of original sin, is a doctrine revealed by God and therefore to be believed firmly and constantly by all the faithful.”[29]Hence, if anyone shall dare — which God forbid! — to think otherwise than as has been defined by us, let him know and understand that he is condemned by his own judgment; that he has suffered shipwreck in the faith; that he has separated from the unity of the Church; and that, furthermore, by his own action he incurs the penalties established by law if he should express in words or writing or by any other outward means the errors he think in his heart.

Now, the first thing to note is that Pius IX declared this before Vatican I defined the papal infallibility doctrine and described the conditions. So, it’s not like Pius IX was following a prescribed format, there was no such prescribed format for him to use. Actually, it could almost could be said to be the reverse: it is precisely because the Fathers of Vatican I recognized that Ineffabilis Deus gave an ex cathedra teaching that they constructed their description of the category the way they did. Almost, but not fully.

The second thing to note is that the Fathers of Vatican I were not intending to express a definite and precise formula that must necessarily be followed in order for the pope to make use of his distinct authority in an ex cathedra statement. We can see this through three points. (1) They did not express the point in exclusive terms, such as we see in mathematical proofs that state “if and only if”, or in other contexts such as law, in which legislators use their authority to create an exception by specifying conditions – obviously the general rule applies generally, except where the conditions of the exception are met. The Fathers were faced with a situation in which the Church had always held that the pope enjoys the capacity to make use of the infallibility of the Magisterium in a distinct way, but there had never been any enunciated concrete and specific modality by which the pope must employ it, (a very definite difference from sacraments, which DO have concrete and specific modalities for performing them, over which the Church does not have any authority to alter in substance). Hence those Fathers were in fact describing the conditions under which a pope’s act enjoys that infallibility, they were not authoritatively legislating the conditions, nor were they merely handing on a precise formula which they had received from the Apostles. What they were doing, then, is describing the conditions under which the pope’s invocation of the power can be recognized as the kind that enjoys infallibility, doing so from the very nature of the act.

(2) The Fathers were by no means intending to suggest, or even give any supportive color to a suggestion, that no prior popes had ever taught something ex cathedra. If they had done so, they would have opened themselves up to the serious charge that they were inventing the doctrine anew (something many outside the Catholic Church have urged), rather than merely passing on what they had received. Given this intent, they would have wanted to avoid like the plague setting forth a formula that defines exactly and precisely the phrasing absolutely required for an ex cathedra statement.

(3) Interestingly, a close examination of their description, and Pius IX’s apostolic encyclical, reveals that they do not match up point by point. Let’s lay out the description in PA, and the elements that most closely match in Ineffabilis Deus, to observe the closeness. First I will lay out the elements of the description in PA, in two groups:

I separate them into 2 groups because the first 6 are expressed AS criteria or conditions, and the last 3 (i.e. 9, 10, and 11) are expressed as consequences. I believe that the last 3 are usable because when they are present in a teaching document they help to indicate the intention in a more clear way, and thus cooperate with the primary 6 items to make the ex cathedra act recognizable.

Now let’s see Ineffabilis Deus and how it lines up. As best I can fit it:

Let me note right off that it is possible for some of these to be a better fit than others, some fit only by implication, or derivatively, and the derivation may take only a step, or several intermediate steps.

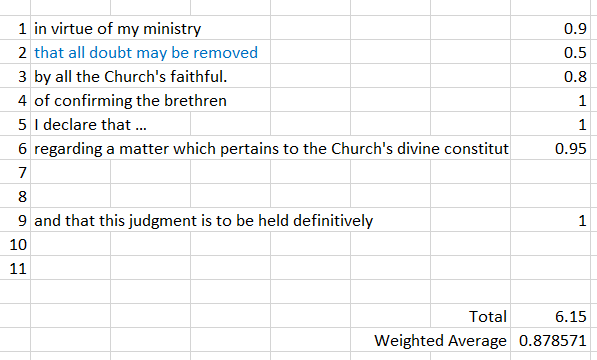

I tried to ascribe to each element a score, representing how clearly and directly it matches up with the elements in PA. For example, if I had to use the same textual element twice to fill in an item, I only grant it in its second location (at most) 50% weight. And if it is by implication, I adjust its weight by the immediacy and clarity of the implication. And if by its implication it seems to detract at all from the criterion, I reduced its weight. This is, of course, rather subjective. In scoring, I required a value for each of the first 6 elements, and so the denominator for the weighted average includes at least 6. And I included a point in the denominator for the last 3 (items 9 through 11) only if there actually is a piece of the text that fits it reasonably well.

Not bad, but not really all that great, either. It is rather obviously missing clear expressions for 1 and 4.

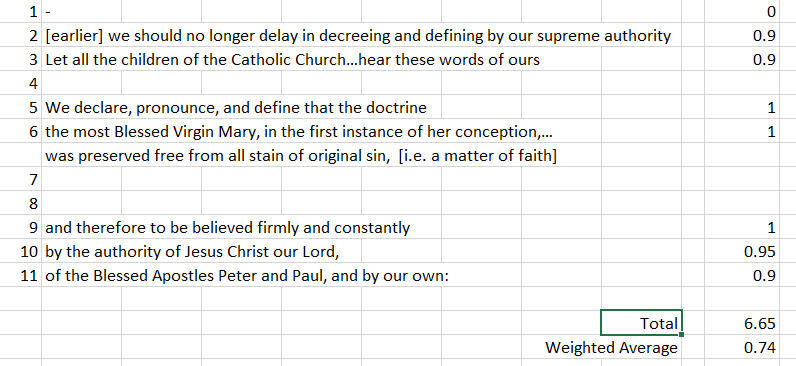

Well, that’s the score for the FIRST act that is universally pointed to as an ex cathedra statement. What about the second? That one was by Pius XII in 1950, with Munificentissimus Deus (MD), which taught that Mary had been assumed into heaven after her earthly life:

For which reason, after we have poured forth prayers of supplication again and again to God, and have invoked the light of the Spirit of Truth, for the glory of Almighty God who has lavished his special affection upon the Virgin Mary, for the honor of her Son, the immortal King of the Ages and the Victor over sin and death, for the increase of the glory of that same august Mother, and for the joy and exultation of the entire Church; by the authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, of the Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and by our own authority, we pronounce, declare, and define it to be a divinely revealed dogma: that the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.

Let’s move to laying it out for match up and scoring it:

Really, not very good at all, and that’s even though he declared this AFTER Vatican I. So, obviously, the concept by which the pope viewed the PA is that it helps us recognize an ex cathedra statement, but does not set forth a formula nor does it authoritatively prescribe precise conditions as mandatory criteria.

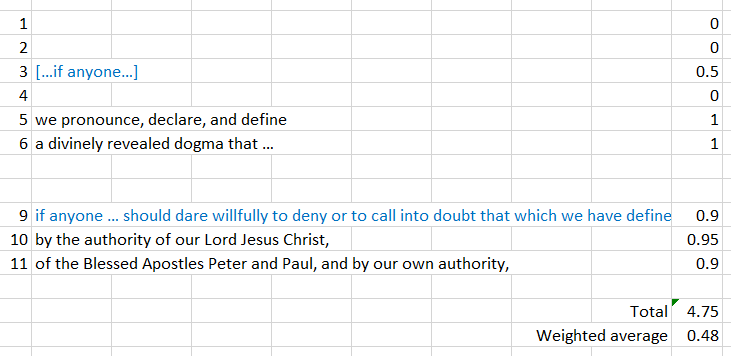

Now, how well does OS match up?

So, actually, pretty darn well. No, it’s not a perfect match, but it’s a darn sight closer than MD. (And, by the way, I was taking pains to be conservative in my allocation of points.)

Now, there is another way to run the analysis, and that is by either the slightly different language in the SECOND Vatican Council’s teaching on the same point (in Lumen Gentium, LG), or by the (again) slightly different language in Canon Law. In Lumen Gentium 25, we have

And this is the infallibility which the Roman Pontiff, the head of the college of bishops, enjoys in virtue of his office, when, as the supreme shepherd and teacher of all the faithful, who confirms his brethren in their faith,(166) by a definitive act he proclaims a doctrine of faith or morals.(42*) And therefore his definitions, of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church, are justly styled irreformable, since they are pronounced with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, promised to him in blessed Peter, and therefore they need no approval of others, nor do they allow an appeal to any other judgment.

Canon Law. 749 §1.

By virtue of his office, the Supreme Pontiff possesses infallibility in teaching when as the supreme pastor and teacher of all the Christian faithful, who strengthens his brothers and sisters in the faith, he proclaims by definitive act that a doctrine of faith or morals is to be held.

When I ran through the same scoring method, I did not arrive significantly different results. In some ways, OS comes out even better.

Nor would I rely solely on a score that treats the elements all as having the same basic weights: It is clear from both V-I and V-II (as well as from the nature of the case) that the essence of an ex cathedra act involves the pope (a) making use of that special authority that was first in Peter specifically and handed on from him to his successors, (b) intending to teach the whole Church, and (c) intending to have the effect of stating what definitively must be held, (that is, both to declare definitively – as not possible to be in error - and to require assent definitively). And when we look at the nature of this kind of proceeding, and compare it to OS, again we find that it matches up perfectly well. When JPII said “my ministry of confirming the brethren”, he was quite clearly calling on his specifically Petrine office, not merely his office as bishop. When he said “to remove all doubt” he was calling on his specifically Petrine capacity to speak definitively, i.e. precisely as entirely protected from error (i.e. infallibility), which is just what it is that removes all doubt. When he said “all the Church’s faithful” he was addressing his teaching to the whole Church. When he said “to be held” he was requiring an assent that is definitive.

So, looked at objectively, without the aid of Cardinal Ratzinger’s CDF “Explanation” of the RaD, (which taught that the position held in OS is infallibly taught and must be held), one can easily come to the conclusion that OS itself is an infallible ex cathedra declaration. Indeed, no other result is reasonable.

Yet seemingly Ratzinger, through his Explanation, did not think OS should be characterized as an ex cathedra statement. But let’s not be too hasty in our conclusions, as Treebeard would say. It is clear, above all, that both JPII and Ratzinger meant to convey that the teaching supported by OS has already been taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium. Yet the distinctive feature of doctrines that have been taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium is that they are not by that method declared infallible under a specific ACT that you can point to that was made at a specific point in time. Their character is that they have been taught by the bishops throughout the world, and since no individual bishop (other than the pope) carries the special charism of infallibility in his office, the bishop’s teachings – however definitively he states them – cannot obtain the character of infallibility from his declaring them. Yet they obtain the character of infallibility in virtue of the agreement of the college of bishops in teaching the same doctrine as to be held. And this, JPII and Ratzinger were at pains to insist upon, had been the case with the holding of OS. Note also that inherent to this “ordinary” structure is the lack of definite-ness about when and whether the overall agreement (i.e. universality and unanimity) of the bishops scattered around the world is such as to cause the teaching to be taught infallibly. There is, then an inherent room for doubt about such teachings as to whether they have met the requirements for being taught infallibly, or when they did so.

Yet, let us return once again to the actual language JPII used to make his point in OS:

Wherefore, in order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter of great importance, a matter which pertains to the Church's divine constitution itself, in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren (cf. Lk 22:32), I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful. [My emphasis]

What is distinctive of the extraordinary acts of the Magisterium – either the ex cathedra declarations by the popes, or the solemn definitions of dogma in an Ecumenical Council of the world’s bishops gathered together – is that one can indeed point to a specific event at one point in time where the declaration was made with that special charism of infallibility_made_manifest, so that not only is it taught infallibly, all doubt is removed. That, indeed, is one of the main purposes of the charism of infallibility by the use of those extraordinary acts of the magisterial office. (Note, also, that by the very nature of the case, teachings that are EVER likely to become the subject of an ex cathedra teaching are teachings that have long been taught by the Church, especially, that have a history that dates back to earliest times, because these are the ones that popes are likely to have the necessary confidence about that they are indeed taught with Apostolic approval (c.f. Ratzinger’s explanation in CDF’s document Donum Veritatis about the role of the pope not to invent new teachings but to preserve what he has received).)

And this, undeniably, was a primary intention of JPII in issuing OS: to remove all doubt. This is not only manifest in the very words of the final formula he used, it is manifest throughout the whole document. But it is only in the EXTRAORDINARY acts that are magisterially protected from error that “all doubt is removed”, because it remains possible to doubt, (of teachings that have been made infallibly taught by the Ordinary Magisterium) precisely on account of the difference between the ordinary and the extraordinary. Hence, in the very nature of the exercise, JPII needed to employ an extraordinary exercise of his papal charism. And, in the very nature of the expressions he used, he actually did carry through the words necessary to express a teaching infallibly (in his own Petrine right and not merely by virtue of repeating what the Ordinary Magisterium had taught infallibly), i.e. as an ex cathedra declaration. He meant to generate the kind of declaration that removes all doubt; the only kinds of declarations that remove all doubt are the extraordinary kinds of exercise of the magisterial teaching office protected from error; only the ex cathedra version of the extraordinary acts is available to the pope acting alone, and he actually used – in full - the kinds of amplifying expressions that ex cathedra declarations use to invoke the extraordinary mantle of infallibility available to the pope.

So, the conclusion that the teaching in OS is in fact an infallible ex cathedra declaration is the most reasonable one.

I can see one additional distinction being offered to make us hesitate: that because the position he taught in OS had already been taught infallibly, perhaps OS rather taught infallibly “that it had already been taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium”. That is, the specific object of the infallibility in play OS had to do, rather, with the character of the doctrine as it had already taught, not its content. I believe that this cannot really work, for two reasons. First, the critical sentence does not have, as its explicit object, the _character_ of the customary teaching. Second, even though both of the two universally accepted cases of ex cathedra declarations were on subjects that (arguably) had already been taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium (it certainly seems that way from the evidence brought forth for them in the popes’ documents), they did not see fit to firmly cement the prior teaching by making the already existing infallibility the object of their declarations. As precedent goes, it appears to be not the preferred manner of proceeding.

(I would say that there is a very delicate balance in play in a system that allows for infallible teachings both under extraordinary acts and via the Ordinary Magisterium. On the one hand, any plausible candidate for an ex cathedra statement is very likely to already be a doctrine already taught infallibility by the Ordinary Magisterium. On the other hand, if you wield too free a hand in either how many, or the manner, of cementing these as being infallible by extraordinary acts of the Magisterium, you run the risk of undermining the whole point of there being the very category of ordinary doctrines that are infallible. One way is simply to start repeating immemorial doctrines in ex cathedra statements. But another way, more subtly dangerous, is to make the object of ex cathedra statements to be the historical character of the immemorial teachings. Ultimately, the real point of the extraordinary exercise of the magisterial authority is not to paint more clearly the historical picture that could determine the epistemological status of the teaching, but to confirm the teaching itself.)

OS was an ex cathedra declaration, and not directly infallible in the thesis that the teaching of the Ordinary Magisterium had been taught infallibly already.

Going back, then, to Cardinal Ratzinger’s CDF Explanation, was it just wrong?

Let’s look at the language, again: In this case, an act of the ordinary Papal Magisterium, in itself not infallible, witnesses to the infallibility of the teaching of a doctrine already possessed by the Church.

Let us recall that there have been any number of papal teachings, ordinary acts of the papal teaching office, which are not infallible in style, and primarily repeat what had already been taught by the Church. In support of their not being infallible of their own character, they don’t claim to settle all doubt. Moreover, they don’t have multiple elements of the other phrases that clearly and closely refer us to the conditions cited by Vatican I and Vatican II for the pope to employ his special charism of infallibility. Clearly, then, in this instance Pope JPII went well beyond the ordinary acts of his papal teaching office in re-asserting and witnessing to the long-established teaching of the Church. So, while it is true that the pope could have employed a non-infallible ordinary effort to repeat and witness to the traditional teaching, that’s not what happened here.

It is my best guess that Ratzinger (and to some extent JPII also) were so intent on NOT OVERTURNING the sense of the existing infallibility of the teaching which it had in virtue of being taught so by the Ordinary Magisterium, that they managed to miss the fact that in OS, the pope’s formal assertion actually satisfied the conditions of an ex cathedra statement in its own right. It is a mere guess of mine that they did so because the Holy Spirit led the pope by the nose.

Recent popes have been almost famously (or, according to some,infamously), reticent to actually take the full authority of their office and teach or bind with finality. Certainly there are other instances where Paul VI and JPII refused to use the full authority of their office when doing so could have settled an issue, and (arguably) failing to use it was so devoid of rational basis that their choices were actually damaging to the Church. One wonders whether they did so from a habitual avoidance of doing things that could give the appearance of being “authoritarian”. It has been, certainly, a widespread illness in the ranks of Church authorities, this lack of making definitive, authoritative acts to support and protect the doctrine or practice of the Church.

At the same time, JPII – certainly as a bishop molded by the experience of being at Vatican II – seemed to be strongly convinced of the primacy of persuasion, that the failures to bring in the dissenters and hold-outs from the truth was a failure of adequate persuasion, and that the answer was better persuasive efforts (cf Vatican II’s Dignitatis Humanae, to which Karol Wojtyla was a _critical_ contributor). This attitude, while it is immensely beneficial to teaching in the missions to pagans, has very little of benefit in dealing with hard-hearted heretics – most of whom (these days) are imbibers of the heresy of Modernism, and thus very nearly impervious to argument, however sound it is. Those who hold error due to bad will do not need better instruction, it is not their intellect that is the seat of the problem.

This is only a guess on my part: JPII may well have been led to imagine that he could issue a letter that addresses the topic in a way that “settles all doubt” by clarifying and distinguishing the truth so that he put it beyond doubt, especially, in clarifying how overwhelmingly strong the evidence was for the already existing infallible teaching from the Ordinary Magisterium. But in the midst of writing it, the Holy Spirit guided his hand (and intention) to actually formulate a binding and infallible expression of the papal authority to settle a question by speaking ex cathedra, and so perhaps what he set out to do and what he actually did were not identical (though they overlapped a great deal, and what he did accomplished in full the original intent). Yes, he did lay out good reasons for Catholics to recognize that the Church had ALREADY taught the point infallibly, but in formal declaration (Ratzinger’s words) he went beyond that mere recognition, and forced the point with an extraordinary act of his teaching authority.

Clarity on this is actually important: (a) because the popes as a class, and the Church in toto, do not want the exercise of ex cathedra declarations to require any precise formula, and (b) we especially do not want to represent that to be an ex cathedra statement, it must SAY it’s an ex cathedra statement. We don’t want to fall into a hole of appearing to assert that no former pope could possibly have exercised their office in ex cathedra statements because they didn’t use a formula that we now think is required norm, and none of them said “this statement is ex cathedra”. Yet, if we are to be reduced to “knowing” that a pope’s statement last month or last year was ex cathedra ONLY because CDF told us, later, that it was, this is really not any better (viz. how do we know that CDF was right?) Hence it is critical that the criteria be the general criteria that apply from the very nature of using such authority on a matter of faith and morals, which are the criteria that PA and LG described: he must be using his Petrine authority, he must intend to teach the whole church and to bind it, and he must intend to make it definitive – i.e. require that all assent to it definitively. And when it has these characteristics, it is an infallible ex cathedra teaching, because that’s what it means to be such. It does not require either that the statement itself call itself “ex cathedra”, or that CDF call it so, precisely because it has its character from Christ’s power, and “not from the consent of the Church”.

So, I would put it as follows: during the year between when JPII issued OS, and when Ratzinger and CDF affirmed its status requiring definitive assent, Catholics rightly would have compared OS to the descriptions of ex cathedra declarations by PA and LG, and rightly would have concluded that OS is an ex cathedra statement. Easily – there isn’t really any gray area about that, it is quite easy to show that it meets the description and the essence of an ex cathedra declaration. In his Explanation, Ratzinger did not address himself to the question “Does OS meet the conditions described for an ex cathedra statement, he addressed himself primarily to the question whether the teaching had already been infallible, and whether assent was obligatory, to which the answer was “yes”. Because he presents not one iota of evidence, and not one scintilla of argument, to overturn the determination Catholics had already made that OS was an ex cathedra declaration, there is no reason to reject that conclusion other than his mere (bare) depiction “an act of the ordinary Papal Magisterium, in itself not infallible” (a depiction nowhere substantiated in the document). And this bare depiction is insufficient to overturn that conclusion, based as it (the conclusion) is on the manifest evidence of the formula JPII used and the nature of the effect he was trying to accomplish. Because the primary thrust of the Explanation is that the obligation to assent to the teaching already existed before OS, and it is unnecessary to that purpose to decide whether OS was an ordinary or extraordinary exercise of the papal authority to teach, his comment can instead be taken as in a way “at a minimum…” In other words, whether the pope was making a statement via his ordinary or extraordinary authority, the teaching itself is (had already been) infallible and definitive assent is required. Hence it was not per se necessary for Ratzinger to establish whether OS was ex cathedra or not, and even if it was NOT ex cathedra the result (the mandatory assent requirement) holds. To sum up:

(1) His primary objective was not whether OS was ex cathedra;

(2) His primary objective did not require settling whether OS was ex cathedra;

(3) He offered neither positive nor negative evidence, nor arguments, to render a justified determination on whether OS was ex cathedra; and

(4) The phrasing of his “an act of the ordinary Papal Magisterium, in itself not infallible” is less in the nature of a conclusive assertion of “ordinary” and “not infallible”, and more in the nature of a postulating expression: even supposing that it was ordinary and not infallible, that is sufficient to conclude that...

Therefore, we should take his comment to comprise an assertion about the obligation to submit in definitive assent, and NOT an assertion directed to or against the well-founded conclusion, which any good Catholic would have reached by that point, that the declaration in OS is ex cathedra.

Comments (6)

I can understand JPII and Benedict wanting to emphasize that JPII wasn't declaring something new. (And in this case I agree that it wasn't something new!) But that sure looks like an ex cathedra pronouncement to this Protestant!

Posted by Lydia Mcgrew | October 28, 2019 8:58 AM

I'll take that as a conditional: if there were such a thing as infallible ex cathedra statements, this one would qualify. :-)

Posted by Tony | October 28, 2019 9:40 AM

Heh.

I was using "ex cathedra" in its role as a social category. Like "duly passed law."

Posted by Lydia Mcgrew | October 28, 2019 2:53 PM

Tony, this is a good presentation of the issues. However, I’m not persuaded of your conclusion that the point of OS mandated a declaration ex cathedra. I agree that Councils and ex cathedra statements can be pinned to a specific place and time; this is indeed what distinguishes them from claims that are true “always and everywhere”. Therefore, however clarifying and infallible OS might be, it couldn’t be ex cathedra for the very reason that it was an always-and-everywhere teaching. If it could have been both, surely Ratzinger wouldn't have hesitated to say so; it would in no way stop him from emphasising the perennial nature of the claim (as I agree he and the Pope surely wanted to do) unless there was some problem with its being both.

Now I don’t know if there is a metaphysical impossibility that would preclude, say, the Pope's invoking Ephesus II and redeclaring Mary to be the Mother of God; but nevertheless, it doesn’t strike me as quite kosher. In a similar way, it presumably doesn’t make sense to declare ex cathedra something that was already taught by a previous ex cat or council or always-and-everywhere.

What, then, are we to make of Pope John Paul’s cathedric language in OS? I would take it at face value: it is a clear and unambiguous statement of a teaching; in this case, a teaching that happens be known as true always and everywhere. The same language could have been used to make clear ex cathedra declaration; it just happens that other relevant criteria didn’t fit in this case. That doesn’t leave any extra wiggle-room for someone to dispute the conclusion — if OS hadn’t been infallible teaching, then JP could not have honestly worded it in the way he did. That is, there is no official formula for a declaration by the ordinary or extraordinary Magisterium; however, the language used by Pope John Paul is suitable for either kind of infallible pronouncement.

Posted by Mr. Green | November 8, 2019 8:18 PM

Thank you for an interesting and worthwhile objection, Mr. Green. I think (if I understand you correctly) that I can't quite agree with you, but I see room for developing both sides more thoroughly. I will try to develop my own POV with enough clarity to advance the dispute.

First, when you use the expression "always and everywhere" I assume you mean to refer to a teaching that is an infallible teaching of the Church in virtue of its being taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium, and NOT having been found in an extraordinary doctrinal declaration? The rest of my remarks will assume this.

I would like to clarify a couple of points about these "ordinary" infallible teachings. First, they are found in the ordinary teachings of the bishops scattered throughout the world. In particular, they are taught by those bishops as "to be believed" or "to be held", not merely as "to be considered" or "to be pondered." The teachings of this sort have been pointed to in a firm way.

However, at the very same time, no individual bishop (who is not the pope) has the charism of infallibility in virtue of his being a bishop, and so when he teaches something in such a manner as he is telling his flock that it is "to be held", he is unable (has not the authority) to teach as "to be held because when I teach it I am infallibly protected from error by the Holy Spirit". No bishop claims that protection of his own teaching, because any one bishop can fall into error.

As a result, the mode under which the Holy Spirit acts to make such a teaching to be infallibly posited to the Church is to maneuver and inspire the bishops so that what they each do individually also falls in with the others so that there is an (effectively) universal agreement among them. So the infallibility is not found in Bishop Hilary, or Bishop Martin, or Bishop Ambrose saying it, but in the (virtually) universal agreement of them.

(Please note carefully that, exactly as in the case of an Ecumenical Council, which does not require absolutely perfect unanimity of a declaration in order to settle a dispute with an infallible extraordinary act of dogmatic teaching, so also the kind of agreement between the bishops scattered around the world need not be perfect. In a Council, even the great dogmatic constitutions typically got at least a few dissenting bishops. That did not preclude the kind of agreement we characterize as "complete". Similarly, it is enough, for an infallible teaching of the Ordinary Magisterium, that it have the agreement of virtually the whole of the bishopric, not absolutely every single one.)

Also, note that while the kinds of teachings that have this character, having been taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium, are ALSO typically found to have been taught always as well as everywhere, in principle once it is true (at any moment in time) that a teaching is taught by all the bishops by a (virtually) universal agreement as to be held by the faithful that agreement among them implies that it IS infallible - and this implies that any later falling away from universal agreement cannot unwind the infallibility. Once infallibly taught, it retains that character no matter how many bishops become heretics on that matter, even if all but one were to do so.

This, by the way, is just the kind of situation in which the Ecumenical Councils operated in order to declare a dogmatic teaching infallibly: a teaching that HAD been taught universally by the bishops (during, say, the Apostolic era and/or immediately following in their first-generation disciples), later came to be doubted and debated among various bishops. The early bishops all taught that Christ was divine, to be adored. They equally taught that Christ was man, like us in all things but sin. But the later Arian bishops were unable to square those two truths and make them cohere, so they objected to the former. The orthodox bishops, in Council (eventually) prevailed on the point precisely by relying on what had been taught universally by the bishops of the Apostolic era and right after. Just because a teaching had been taught infallibly doesn't prevent it from becoming a matter of (new) dispute, and in that situation it befalls the bishops in Council to declare it as a solemn definition (i.e. as an extraordinary act) confirming what had ALREADY had general agreement in an earlier era. They never declare these things as new truths but only as the old truths that had been handed down to them.

Thus, so far from making it a truth unfit for an extraordinary infallible confirmation, it having been taught by universal agreement at some earlier era is exactly the sort of pre-condition one would expect to have for any new solemn declaration that is infallible.

And this procedure is EXPLICITLY present in Ineffabilis Deus in which Pius IX declared Mary was conceived without sin: he consulted the history behind the teaching, and found that it had been taught with a universality that was quite profound. He similarly consulted with the then current bishops, and they confirmed their agreement with a remarkable degree of confirmation. And in those conditions he felt well prepared to declare the teaching via an infallible ex cathedra teaching, thus settling the matter for all time.

My second point regards the nature of what it is that drives a pope to use an ex cathedra declaration. For, he has to have a reason to feel it opportune to make use of his authority in this way. One of the most suitable reasons is to SETTLE DOUBTS that are (now) being raised. And, most significantly, to settle doubts where no honest cause for doubt exists, because the Church already has a certain truth available to answer the question. In other matters, matters of speculation or matters still under development, the Church prefers (rather strongly, in most cases) to take a hands-off attitude, and to let the discussion go forward in a more or less free manner: let the chips fall where the best argument comes out eventually, over time. Sometimes MUCH time (she can afford a several-centuries dispute). But when it is a matter about which the Church at one time already spoke clearly and with certainty (via the Ordinary Magisterium), a new dispute will probably be due to some kind of undue and probably uncharitable approach to a question or issue, on which one side (at least) is making hay out of unwise, inappropriate, or unfair arguments to cast doubt where no doubt ought to exist. In that situation, good Catholics who are not well educated (i.e. most of them) may not be able to sort out which side has the right of it, so they need the authority of the Church to guide them. In such a situation, then, the pope can exercise his office of confirming the brethren in their faith by stating definitively the truth that had (at one time) been taught universally in the ordinary way, although (now) is taught less unanimously.

Consequently, I quite firmly dispute the theory that a pope cannot or ought not teach by an extraordinary act what had already been taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium. Quite the contrary.

While Vatican I was intent on marking the papal capacity to teach authoritatively in its "ex cathedra" declaration, Vatican II was intent on making known explicitly what had been known more implicitly earlier about the bishops as a whole: viz, that even scattered around the world, they participate in the teaching office of the Church in such a way that the Holy Spirit can employ them, and guide them, so that ALL TOGETHER they teach infallibly. This had never before been stated so explicitly. Pope JPII and Ratzinger were both "men of Vatican II", and it is easy to believe that both of them wanted to be sure not to undermine this (recent) teaching of Vatican II which upheld the teaching authority of the bishops. You find this all over in Ratzinger's Explanation. What you don't find is one single shred of is an argument purporting to establish that OS was not an ex cathedra declaration. It just isn't in there.

Finally, I would note that in describing the characteristics you will find when a pope exercises his authority and charism in an ex cathedra statement, none of V-I, or V-II, or Canon Law refer to the teaching as one that has not before been taught infallibly under the Ordinary Magisterium. Nor is there any language in those passages or surrounding them that suggests or implies it. And further, there is nothing in the nature of the extraordinary authority found in a Council or in the pope that prevents that authority to address what had already been taught by the bishops under the Ordinary Magisterium. The very nature of the case allows for the kind of elevation of awareness that occurs through the extraordinary act, because it was not (before) readily and manifestly certain that the teaching had already been infallible.

Posted by Tony | November 11, 2019 1:55 AM

I suggested a possible reason above:

Throughout his papacy, JPII illustrated a very decided lack of willingness to employ the full force of authority vested in him as Peter's successor, both in matters of teaching and in matters of jurisdiction. For example, he had the power and authority to cut short the entire disagreement and very nearly all of the arguments of the Lefebvrists at the stroke of a pen: they argued that while Paul VI may have intended to end the right of priests to say the Mass according to the old form, his actual legislation didn't do that, because (as an immemorial custom) it needed a DIRECT abrogation to end their right to use the old form. Well, he could have directly abrogated the right to say the old Mass with a one-sentence papal bull. On the other hand, when he wanted to throw a rope and life preserver to the not-hard-hearted Lefebvre sympathizers who didn't want a full break from Rome, instead of simply admitting that Paul VI had failed to outlaw the use of the old Mass form and therefore all priests could use it, or giving them by direct positive legislation the same permission, he rather gave them the Ecclesia Dei Commission and a spluttering little rubber duck-sized help that was nearly useless, and only AFTER 15 years of talks with Lefebvre failed - talks that could have NOT failed with simple application of papal power.

Similarly, after at least 15 years of efforts to require meaningful and systemic reform from the Jesuits, under JPII the Vatican effectively just caved in to the Jesuits' "demands" to have their own choice (even if second or third choice) as Superior General, and he accepted in effect a Jesuit leader who was willing to mouth platitudes while changing nothing of substance. Instead of either simply putting a new man at the head of the order, or forcing changes directly, or suppressing the Jesuit order altogether. As a result, at this point only the latter is plausibly a solution, and now two whole generations of Jesuits who could have been rescued by Vatican power applied where it was needed have been turned into modernists.

My point was a suggestion that JPII didn't actually set out planning to use an ex cathedra declaration (because that was not his managing style), and that the Holy Spirit allowed him to not recognize that's exactly what he penned when he used the phrases "in order that all doubt may be removed" and "in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren" and "that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful". Undoubtedly he and Ratzinger would have conferred on the whole idea at great length before he wrote it and before he issued it, so (if my suggestion were to have any value at all) then arguably the Holy Spirit would have done the same to Ratzinger in allowing him not to recognize in the phrasing that all of the requirements of an ex cathedra statement had been met, and allowing him to focus instead on JPII's original idea which was not to declare it as ex cathedra.

Interestingly, if OS was meant only to point out how well the teaching had satisfied the criteria for being taught infallibly by the Ordinary Magisterium, then it was actually less adequate to that purpose than Paul VI's Inter Insigniores, which makes the case at greater length. The fact that some people had continued to teach that the matter was still an open question, after Inter I, shows just exactly WHY it is that popes can issue an ex cathedra declaration that by an extraordinary stamp seals a teaching already infallible under the Ordinary Magisterial teaching.

Posted by Tony | November 11, 2019 6:03 PM