An innate interest in arguing over Lists appears present in most, and pronounced in many male members of our peculiar creature called man. Men will throw themselves into animated discourse over such matters as The Best NFL Quarterback (Elway), or The Greatest Basketball Player (LeBron), or Greatest English Prose Stylist (Wodehouse), laying out Top Threes and Top Fives and Top Tens with notable vigor and persistence. Frequently the females of the species can be observed on the fringes, bedecked with wry smiles or affecting harried cynicism.

Speaking for myself, I enjoy the mischief of the Top Three Presidents list: in particular, I like throwing Reagan in there with Lincoln and Washington, and then waiting, with amused anticipation, for the reactions.

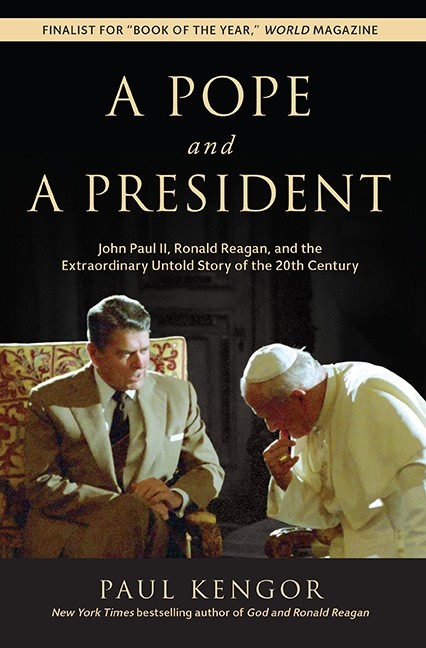

The book under review here, an absorbing study composed by Prof. Paul Kengor of Grove City College, is part of the growing body of historical assessment which is making that mischief no longer effective as such. Because, it turns out, there surely is no mischief in adding to the list of the Greatest Presidents, our Republic’s greatest peacemaker. Lincoln and Washington both fought and won wars -- just wars, I think -- but still cruel and awful confrontations that left indelible scars, bitterness, and many other evils in their wake.

Reagan achieved victory without war; and having done so he prevented incalculable evils.

+++++

It is the burden of Prof. Kengor in this sizable but elegant volume, to demonstrate that few allies in this peaceful victory proved more valuable to Reagan than Pope Saint John Paul II.

Upon diving in, the reader of A Pope and a President will immediately find himself riding the splendid narrative currents of something extraordinary: A Catholic-Protestant alliance without historical parallel. Aspects of this tale have been related in many fine historical works over the past two decades; and we might say that the general lineaments of it are well known in a hazy kind of way.

Millennials who came of age after these men’s deaths -- at least those possessed of any sense -- do know that Reagan won the Cold War, that John Paul II was a great pope, and that both were lifelong and courageous anti-Communists. Most, likewise, understand dimly that all this implies considerable honor to both men, honor that is even granted, however grudgingly, by folks who admire them little in other matters.

But declare to an intelligent, well-read young American, “It is clear that Ronald Reagan was far superior to Franklin D. Roosevelt, for this reason alone: that he won his victory without throwing American soldiers into a bloody world war” -- say that sort of thing, and you’re liable to cause a bit of a start. Add to that startling statement the further one that perhaps Reagan’s most shrewd and effective diplomatic enterprise, in the massive undertaking to peacefully wreck the Soviet Union, was uniting the largely Protestant nation he led, to the diplomatic policy of the Vatican under the Catholic Pope in Rome: again, I submit that you will notice folks’ eyes widening in surprise.

To be sure, several key American figures in this enterprise were devoted Catholics, chiefly National Security Advisor William P. Clark and Director of Central Intelligence William J. Casey; and Reagan himself exuded a natural ecumenism, borne in part out of his heritage from a mixed-faith household. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine an American Protestant more well-suited to this ecumenical alliance with Rome. So the saintly Pole in the Chair of St. Peter, whose generous heart ached for all men oppressed by the marching madness of Communism, found in this American a kindred spirit providentially bereft of the common Protestant suspicion of Roman Catholicism. These details, in my estimation, have never been so ably drawn out and set in proper perspective, than in this volume. As a result of his painstaking assemblage of documents, witness recollection, and prior scholarship, Kengor’s sagacious conclusions ring true. He presents these conclusions modestly, regularly acknowledging uncertainty or contrary interpretations; but perhaps a bolder formulation of some of them will convey the kind of historical synthesis we are dealing with here:

+ Like the Pope, President Reagan took the Fatima Mystery very seriously. He never evinced skepticism, much less hostility, toward the mystical and Marian side of Catholicism. This is a remarkable fact: Of how many low-church Protestants, raised in rural America, could the same be said?

+ With their attempted assassination of Karol Wojtyła, a mere six weeks after Reagan likewise survived an assassin’s bullet, the Communists added to philosophical and strategic concurrence, that personal solidarity between Pope and President, which made the diplomatic partnership something much deeper -- something perhaps better described as a Liga Sancta. Reagan called Wojtyła his “best friend.” Communist treachery consummated its doom in a true friendship borne of solidarity.

+ Since the great Pope supplied unmistakably Christian witness to the alliance, while Reagan, despite sharing the Christian faith, was constrained to operate as the secular leader of a pluralist Republic, the diplomatic effort against the Soviet Union’s machinations took on unique qualities of both catholicity and Catholicity. This, too, is astounding; and far too little has been made of it. Only President Reagan -- the man who called the USSR the Evil Empire to Protestant pastors -- could have achieved the required consensus among Americans, including above all Protestants, to permit the Holy See to speak for Americans, at least to the extent that the Holy See spoke in defiance and condemnation of Communist tyranny. I will concentrate the thing down to its most explosive core. Ronald Reagan did what John Kennedy was accused of being prepared to do: put his policy for the country in the service of Rome.

+ And what is it that Reagan’s policy served? Nothing less than the greatest work in the cause of peace and justice of the entire 20th century. The peaceful collapse and discredit of the wicked system of Marx and Lenin.

Here I have expressed the ideas in very bold strokes, though I do not believe I have exaggerated. The historical achievement just is that significant. Karol Wojtyła and Ronald Reagan cobbled together a Holy League, and carried it to victory by largely peaceful means. What American, what Pole, what Catholic, what Protestant, what lover of peace, can fail to marvel at and give thanks for this?

If my syllogisms are sound, then the further conclusion that Reagan is in the Top Three American Presidents, far from being mischievous, is actually closer to the category of no-brainer.

It should be added that there is much left to learn. Many American National Security Council documents are still redacted, and almost all of the Vatican’s sensitive material won’t be available for a long time. Prof. Kengor was able to dig up, chiefly at the Reagan Library, American memos relating to John Paul’s private letters to Reagan, memos which themselves are very interesting; but the substance of what the Pope actually wrote is still completely blacked out. The Roman Catholic Church maintains a long and patient perspective. It is not too much to suppose that most of us now living will go to our graves, before the text of the Pope’s letters to Reagan (regarding such crucial matters as how to counter the Soviet crackdown on the Polish Solidarity) will be released; but rest assured that historians yet unborn will be itching to read them when the Church finally does release them.

And then there is the fact that Reagan and the Pope met in private numerous times. There were no recordings. Bill Clark preserved a strict “no-notes” rule for matters surrounding his diplomatic work with the Vatican, so even many secondary details cannot be retrieved except in memories, and there are few surviving possessed of those.

It fascinates the attentive reader to discover how often crucial moments, meetings, or statements were missed by the contemporary press. Reagan and the Pope met in Fairbanks, Alaska in May of 1984: press reports were scarce. Very scarce. Even in Miami, three years later, when these men met formally on American soil, the secular journalists show more sullenness than curiosity.

So somehow, at the dawn of the digital age, press reports are scarce about when an American Protestant President, after a brief summary of the ministry of his counterpart, uttered these words, standing next to the Slavic Pope sitting in a Latin Chair:

“Far more can be accomplished by the simple prayers of good people, than by all the armies and the statesman of the world.”

The man who spoke these words was regularly derided as a warmonger by the incurious journalists. The suspiciously inclined might suppose that the Western Press leaned the wrong way in the Cold War. Especially it’s spiritual content. These fools missed the big stories. Even after the Soviet Union is gone, Reagan meets personally with the Pope and Prof. Kengor can only find about six total paragraphs in the English-speaking press. Really weak.

The Warmonger Calumny persists on the Left today. Academia is the last bastion of lazy Reagan slander; and the dogmatism with which it is propagated has the effect of perpetuating the want of curiosity. Even now, reflection remains minimal on such mysterious delights as that Reagan insisted on “Ave Maria” being sung at the National Cathedral on the occasion of his passing. Surely even secular journalists realize that Catholics are devoted to the Hail Mary and Protestants narrow their eyes at it, right?

The chief virtue of this book lies in its meticulous moderation as historical investigation. Prof. Kengor never pushes his view too hard, and he simultaneously (a) shows us his work, while (b) inviting future inquirers to evaluate his assertions and modify them as facts dictate. Having approached his subject with modesty, his conclusions settle in the brain and only some time later detonate with ramifications.

This reviewer has a day job, but it sure looks like interested historians who read Russian, Italian, Bulgarian, Turkish, and Polish have some superb veins of research, sitting like treasure right in front of them. All it takes is hard work. Let’s have Kengor’s conclusions assessed by scholars; let’s estimate their weight in light of future developments. The current crisis in Catholicism throws back a dark shadow; the scumbag McCarrick makes an appearance in this volume. A fair criticism might ding Wojtyła for making foreign affairs more important than actual governance of his Church, with internal serpents maneuvering everywhere. Reagan, too, was kind of clueless about the internal rot in America; he thought the thing amounted only to a crisis of confidence, not a crisis of moral integrity.

Even in light of that, if future scholars confirm even the basic outline of Professor Kengor’s history, they will have confirmed a Reconciliation, at the level of both great statesmen and simple folk, crossing the divide of the Reformation, which is without precedent over these last 500 years.

So everyone should acquire this book, read it, and then decide whether my Top Three Presidents List is defensible. The mischievous among us will be left to assert, with a grand flourish, that Reagan the Peacemaker actually earns top honor.

Comments (10)

Both John Paul and Reagan were great men.

However I have a comment about Vatican II that is maybe not so relevant your your post. I saw the book that came out of Vatican II and I thought it was well done. But now it is looking to me that the Catholics that were dismayed maybe have actually been more accurate. Edward Fesser also I think has the same opinion.

Not everything done by great men always results in things that are so great. I am thinking of the war between Athens and Sparta that Pericles wanted.

Posted by Avraham Rosenblum | November 26, 2018 3:58 PM

This is true. However, I think that what Paul shows us above is a picture of a possibly great man confirmed precisely in virtue of having done a great thing, and done it exceedingly well: not only the winning of a great war, but winning it without the horrors of a hot war.

Whatever the majority of the Council Fathers thought they were doing at the time in voting on the documents, it is now clear (and has been for some 40 years) that those who engineered the final documents intentionally crafted huge mine-fields of ambiguity with which they would manipulate church practice after the Council. Those ambiguities were not necessary in order to produce the good that the Council Fathers were directing their attention to, they were extraneous to such goods. Hence while the words of the Council did indeed have a great deal of truth to teach, they were so encumbered with detrimental verbiage that lent themselves to obscuring the light of truth by manipulators that in effect we would have been better off without the Council. In my opinion, of course. I know that numerous prelates (even good ones, I mean) relate to VII and refer to it in almost glowing terms, but even for them I wonder whether they have asked themselves whether they would be saddled with so much basic, even remedial teaching and other work under such difficult conditions if the Council had been less verbose and more clear.

Posted by Tony | November 26, 2018 7:24 PM

Dr Kelley Ross also in fact noticed the problem of ambiguity in the documents. I have to admit that when I saw the book of Vatican II I was not thinking very deeply

Posted by Avraham Rosenblum | November 27, 2018 7:39 AM

My feeling about the whole thing of Vatican II is from an outsider's point of view. However just to add my two cents worth, I think going back straight to Aquinas and Augustine makes a lot of sense. [There has been some great thinkers since then, but Ed Fesser makes a case that all the modern philosophical issues were already taken care of long ago by Aquinas--and though I have not looking in that carefully, it still seems to have a high probability of being correct from the little that I have read.]

Posted by Avraham Rosenblum | November 27, 2018 8:20 AM

Paul, I have to say that I loved this posting. I had no idea President Reagan was quite so welcoming to Catholic sentiment, though I did know that he was not at all hostile to Catholicism the way many Protestants are. And while I was well aware of Reagan's central role in winning the cold war / war on Soviet Communism, I had not thought to compare it in a direct way to the successes of FDR, Lincoln, or Washington. That's a pretty nifty concept. Certainly it is difficult to estimate the evils we would have been faced with by the 2000's or 20teens if Soviet Russia was still in place, but they would be many and severe.

I do remember living in the Washington area during his presidency, and seeing and feeling the whole conservative movement taking a breath of fresh air. Pretty much to a man, they acted the way a man feels when he has been laboring under a grave mental burden for too long, when the burden is lifted and set aside. The "Whew" of relief was palpable. (Perhaps too much so: not enough was done, arguably, to cement in the gains made in sensible changes that Reagan's years brought. I think many more conservatives than just Reagan failed to realize the moral turpitude that was gradually endangering the common good and even the hope for political solutions to our political ills.)

Posted by Tony | November 27, 2018 10:52 AM

Paul, I think the greatest practical question now facing us is this: How can/could Reagan's peaceful victory be replicated in our own time? Or can it? Would there be any way to approach, say, North Korea or Saudi Arabia in a similar way in foreign policy? What would that look like? Are there ways in which, without the warmongering of which Reagan was falsely accused, we could apply "tough love" to nasty foreign regimes in our own day and achieve any of the following--less oppression for their own citizens, maybe even something like freedom, greater security for Americans at home and abroad, greater safety from invasion for the neighbors of these powers (such as South Korea)?

I'm under no illusions that, of all people, Donald Trump has the ability to craft such a policy. But just occasionally he actually listens to decent advisers, and some of them might know how to do so, if he would listen. Thus far I don't think we've found "it," whatever it is. But it would be great if we could.

Posted by Lydia | November 27, 2018 10:59 AM

Thanks, Tony. I really think both American Catholics and Protestants have not yet (if you can believe it) truly appreciated Reagan's supreme greatness to serenely and diplomatically close the Reformation divide. His understated efforts at unity and reconciliation ring down to us now. A superb example for all Americans; and let me add that plenty of people who call themselves Reagan Republicans today are warmongers in a way he never was. That's not on him but on them.

Lydia, such great questions. The plain fact is that Reagan was of the Cold War era; but his greatness as a peacemaker was to look beyond it. The man held fast to the view that Americans and Russians really have no permanent quarrel. And why should we? He was right.

How to apply his example is a real challenge.

Posted by Paul J Cella | November 27, 2018 3:39 PM

Fair enough: From the time of Peter the Great, Russia was (with varying success) attempting or willing to be part of Europe and Christendom and "the West", and to borrow from that historical, social, and theological patrimony. And until 1917, Russia had no essential quarrel with America. With the demise of what is reasonably considered a mere soviet tumor on Russian culture, we can return to a more interdependent / amicably competitive relationship. In theory.

The same is more difficult to apply to some others, such as Saudi Arabia, where the theological underpinnings of culture have stewed an anti-Christian world-view for 13 centuries. And both China and North Korea never were part of "the West" in any rational sense. While China is not as belligerent as North Korea, they also have a much deeper history and culture independent of any Christianizing influence that makes them a tough nut to deal with. One doubts that "Nixon went to China" was the result of a deeply philosophical and moral insight by which Richard Nixon set out to bring a humane and Christian anthropology into a sphere of influence thirsting for enlightenment by the patrimony of the West.

Posted by Tony | November 27, 2018 5:13 PM

Yet one generation after Reagan, an American can lose his job simply for denying that a man can be a woman. Having lost battle after battle, the Reaganite conservatives could not even conserve ladies' bathroom and are reduced to make conservative case for same-sex marriage. The heritage of the energetic Reganite foreign policy has been disastrous in Middle East. Even Reagan winked at Pakistani nukes and his encouragement of Moslem jihad against Soviets backfired severely.

The Reaganite fusionism of conservatism with libertarianism, an inherent impossibility, as Russell Kirk saw, hindered social conservatives and is responsible for almost all their political and judicial defeats.

And, as many believe, that the modern progressivism is just Marxism under another guise, we can not even claim that Reagan won the cold war.

Posted by Mactoul | November 28, 2018 5:55 AM

modern progressivism is modern "regressivism."

Posted by Avraham Rosenblum | November 28, 2018 6:10 AM