Despite its scientific pretensions, political economy amounts to nothing more than the integration of wealth and assets across generations. This wealth and these assets are inexorably subject to decay. They perish, and the effort of integration remains uncertain, tenuous and fraught.

Rather than emulating the complacency of the astronomer, who operates with confidence that Rigel or Polaris, while not strictly speaking eternal, nevertheless may be studied on the postulate of functional eternity, the political economist should swallow his pride and adopt instead something reminiscent of the humility of the gardener. A gardener takes nothing for granted. The caprice of the world rises foremost in his mind. A ill-timed frost carries the potential for ruin. Drought may parch the most fruitful land; flood may inundate and destroy the most careful plantings.

The introduction of hard-science pride into political economy resembles the folly of the gardener who thinks that mobile weather apps will preserve his fruits and shrubs against the elements. Agonzied exclamations — “but my phone said it would stay above freezing!”— will be answered by supreme indifference.

The astute gardener knows, however, that much depends on his enterprise. He is idle no determinist. Observation, attentiveness, well-timed exertion, cooperation, intuition, implementation of prior discoveries: by these ancient contrivances, he may meet with some success.

The astute economist, likewise, knows that the root of all wealth is human enterprise — the application of intelligence and hard work to the natural resources of the planet. Wise stewardship preserves and expands the capital stock, which arises out of the God-given fruitfulness of mankind.

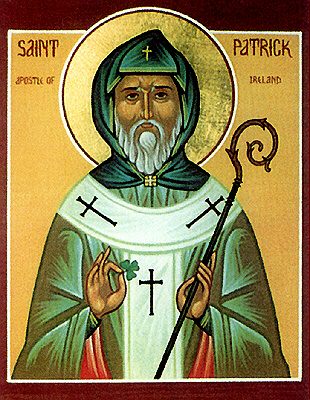

There were few greater geniuses of political economy than “the great company of Irish saints” of late antiquity, whose faithful supervision of the resources available to them, in the dying anarchy of the Roman order, preserved against ruin and decay the human wealth of the ancient world. These men, among whose number we include the enigmatic and beloved saint celebrated today, give to a hackneyed modern phrase renewed life and vitality. They were the supreme wealth managers of our ancestry. No one ever applied the gardener’s humble wisdom more piously to the integration of wealth across generations, than the monks of old.

What Whittaker Chambers wrote of St. Benedict, and of his great work in southern Europe, we may also say of the Irish saints of northern Europe:

At the touch of [their] mild inspiration, the bones of a new order stirred and clothed themselves with life, drawing to itself much of what was best and most vigorous among the ruins of man and his work in the Dark Ages, and conserving and shaping its energy for that unparalleled outburst of mind and spirit in the Middle Ages.

What these saints demonstrate for us today is the narrowness of our notions of wealth, prosperity, and economy. The academic discipline which takes for its title the latter word has all but forgotten the foundation of its subject-matter: the fruitfulness of human beings, as they pass their resources, material, intellectual, spiritual, from generation to generation.

The nine-thousand-year lease enjoyed by the Irish brewer whose product many of us will joyfully imbibe today, suggests a sounder horizon for thinking about economic prosperity: not the next paycheck, not the next quarter’s evanescent earnings report, but the true wealth of nations, unto to the next age, and the age after that.

The Celtic Church, though it ultimately submitted to the authority of the Papacy, had its own character and integrity. It had never known the secular, and was largely isolated from the ecclesiastical power of Rome — a fact that became manifest when St. Columbanus came to France and quarreled with the worldly and often decadent Frankish hierarchy. We do not know precisely how these quarrels were settled, but we can reasonably guess that the settlements, which avoided what would have been a disastrous schism, were the fruit of the holiness of Columbanus and Gregory the Great, who then sat on the Chair of St. Peter.

There is a lot of contempt, in modern thought, and in modern unthinking prejudice, for the idea of monasticism. But we often forget about monasticism that it was a powerful an engine of political economy in a world where political and economic stability had vanished. In monasticism Western man found a way to be productive again; and in monasticism we see the early beginnings of that power over material forces, that stewardship of the riches of creation, that made us — the men of the West — masters of the earth. That this power has perhaps been the single most calamitously abused thing in all of the bloody history of mankind does not diminish the astonishing humility and piety at its roots. It was the piety of the simple gardener, carefully assessing the soil, patiently removing the weeds, observing, learning, submitting to forces he never imagined he could control.

And I might be forgiven for the occasional fancy that all our machines and computers and efficiency are but a slow decline from the awesome achievement that the Irish monks made visible in the gardens of the great monasteries.

So on this day when we celebrate the man who drove all the snakes from Ireland, let us also recall his Irish brethren, who so filled the world with their own “mild inspiration,” and made us who we are.

__________

Revised and expanded from older posts.

Comments (6)

Nice thoughts, Paul. One thing that has long made me wonder is the long (and usually completely hidden) history behind a great many of our existing take-it-for-granted wealth. Who, for example, first thought of trying to take coffee beans and making a drink out of them? Who perfected the drink by a tiny bit of sugar and cream, so that we have a marvelous morning beverage. How many generations of tinkering did it take to go from the first person who said of fermented juice not "it went bad" but "it went GOOD" to the wine or beer of recorded history? How many uncelebrated geniuses are there in that history who have added their own incremental improvements which we all benefit from today? Who was the first person - in an age without refrigeration - to think of "preserving" milk by letting it get "cultured", and who do we have to thank for the generations of development bringing us parmesan cheese?

If one were to measure the value in economic terms of all of the stored knowledge, experimentation, tinkering, and development of what we think of today as BASIC goods, it would be staggering. In practice, it would be effectively incalculable, in that the people of the world would be willing to give MORE than the entirety of acknowledged wealth to have all of what that storehouse represents.

As for our great Irish saints: thank God for them, for we are the beneficiaries of their foresight, their 'mild inspiration'.

Posted by Tony | March 17, 2018 8:22 AM

Fantastic point, Tony. The idea could be expanded almost without limit, in some cases to comical effect. The first man to conceive of frying a catfish was either a genius or a lunatic. Most of the components of good salads could not have instantly recommended themselves for their tastiness. I've never been a smoker, but consider the antics of the knuckleheads who first discovered tobacco; how many herbs did they go through before they discovered one that didn't produce violent convulsions and burning eyes? More broadly, we regard the cultivation of wild strains of maize, soybean, etc., into commercial crops to sustain cities as huge step in human development (with some scholars even being so bold as to condemn it as a degradation); but we easily forget that no one knows who or how it was done. The whole huge achievement is concealed in the mists of time.

Posted by Paul J Cella | March 17, 2018 12:52 PM

"There is a lot of contempt, in modern thought, and in modern unthinking prejudice, for the idea of monasticism."

Actually not so much. While meddling priests are justly despised, monks are overwhelmingly good neighbors and are usually welcome. Here in live and let live California there are many retreats of all persuasions east and west - four or five that I know of are within two or three hours drive of chez moi. In the Los Angles area there are quite a few.

"...no one knows who or how it was done."

The who is lost but the how was likely the method advocated by a mycology prof I had back in the day - "test a sample on the neighborhood children." Going from wild maize to a more productive crop is simply a matter of selection.

"(with some scholars even being so bold as to condemn it as a degradation)"

The development of agriculture allowed the development of parasitic social classes - priests, nobles, etc. It is only recently and always with difficulty that the resulting surplus has been fairly apportioned.

Posted by al | March 17, 2018 2:34 PM

>> "There is a lot of contempt, in modern thought, and in modern unthinking prejudice, for the idea of monasticism."

> Actually not so much.

Exactly Al. Not so much. If anything, the reverse is true in this romantic age. Assertions of contempt at this point merely reveal foils mimicking persecution complexes. I've gone through the monastics, and what their modern adherents claim for them. In the end I'm nonplussed. I give them their due for what they tried to do, and I'm highly skeptical of what their modern adherents uncritically attribute to them. As God intended, of course. Nothing ever changes. I'm completely sympathetic to modern attempts to understand and/or mimic the monastics, yet highly critical of these folks to the extent to which they aren't critical in their understanding and analysis.

Posted by Mark | March 17, 2018 11:16 PM

Paul,

That is a fine read - well written food for thought.

Posted by Paul J Cella | March 18, 2018 12:06 AM

Good post, Paul. I've just been thinking about the difficulties in economic reasoning and the fact that so often it's hard to figure out exactly *what went wrong* when some economic reality seems "off." Or even, to put it more neutrally, what the causes are of some economic phenomenon that one in fact thinks is regrettable.

I suppose the gardening analogy would be the difficulty figuring out why the peach trees didn't have a good yield this year.

Posted by Lydia | March 19, 2018 5:26 PM