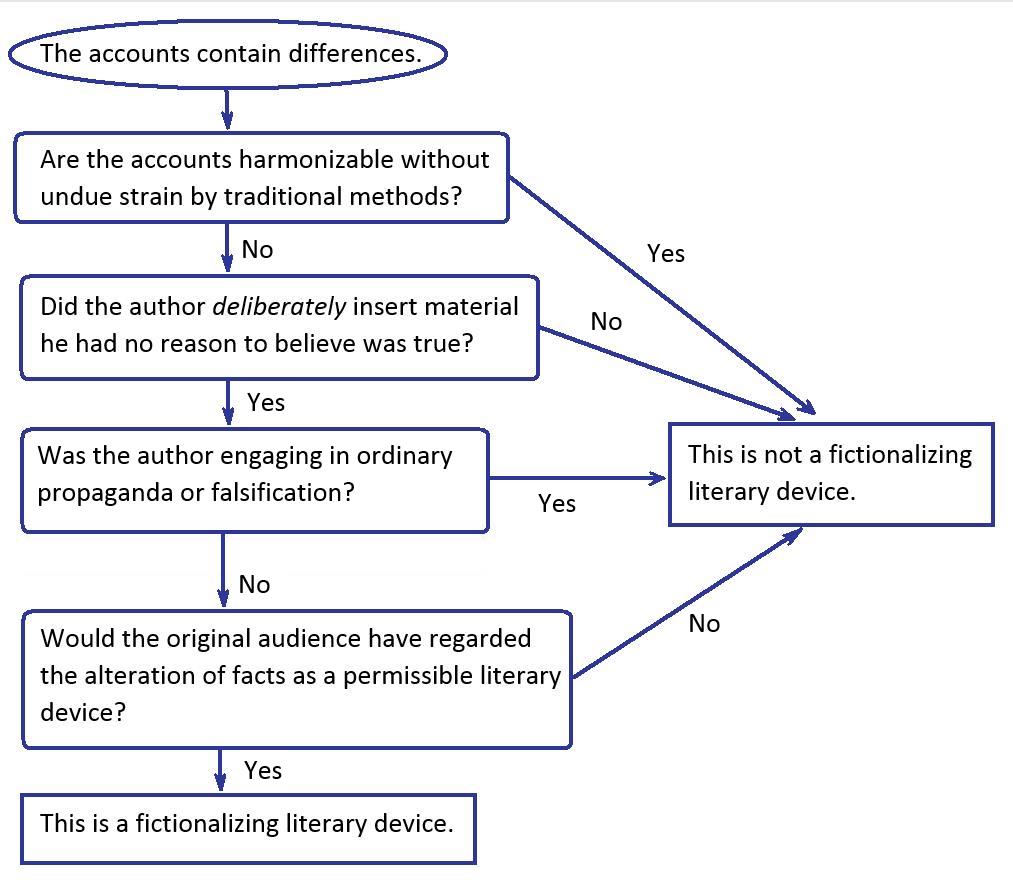

This is just the first entry in which I intend to display this flowchart. You'll be seeing it again! Here I want to discuss the flowchart itself and how it applies both to biblical and to non-biblical texts. The intention is to provide a framework for evaluating the claims of Richard Burridge, Michael Licona, and various Roman history scholars concerning the alleged presence of fictionalizing "literary devices" in an ostensibly historical work.

To begin with, I should explain what I mean by "fictionalizing literary devices," since the phrase is my own. In broad terms, I mean by that phrase an author's deliberately including in a putative historical work incidents, details, or speeches which he has (at least) no reason to think are accurate or even knows are inaccurate. I also mean, if the action is to count as a literary device as opposed to ordinary truth embroidery, deception, etc., that such an act of fictionalization was something the author believed he was allowed to do without violating the expectations of his readers as to his accuracy and truthfulness and (moreover) that he was right about that--that there really was such a convention in the social context in which the author was writing that this type and degree of fictionalization would have not caused surprise or consternation among the majority of the readers of the work, because it was expected of that type of work. Here are a few definitions from Licona's own book that provide paradigm examples of what I mean by fictionalization:

Transferal: When an author knowingly attributes words or deeds to a person that actually belonged to another person, the author has transferred the words or deeds.

Displacement: When an author knowingly uproots an event from its original context and transplants it in another, the author has displaced the event.

I note in passing that most of the time, though not with perfect consistency, Licona uses the term "displacement" to refer to cases where he is alleging that the author definitely implies or even states that an event took place in a different context from its original context. In other words, most of the time he is not talking about cases where, according to him, the author merely narrates events out of chronological order. The distinction is crucial, and Licona's failure to admit the importance of the distinction and to maintain it creates some confusion. In one egregious instance he says that there is "displacement" when Plutarch literally pauses to tell the reader that he is jumping forward in time to narrate an event that happened later and fit together topically with what he was talking about. Licona then speaks as if this is "displacement" and so are cases where, he alleges, the author deliberately made it look like the event really took place at a different point in time from the time that it really happened.

Conflation: When an author combines elements from two or more events or people and narrates them as one, the author has conflated them.

(All of these definitions are from p. 20, Why Are There Differences in the Gospels.)

Another example of fictionalization would be simply inventing a speech for an historical character when one has no reason to believe that the character either said those specific words or expressed those ideas in something approximately like those words.

Obviously, "crafting" an entire scene or incident counts as fictionalizing. So would making up a detail, such as a number or a name, that one has no reason to believe is accurate, and inserting it into the story just to make the story more vivid or interesting.

But here I want to emphasize again that, although I would count any of these as fictionalization, it doesn't follow that I would count them as "literary devices" even if they occurred, since they might just mean that the author was careless about truth or liked to embroider his tale or engage in propaganda.

Here are a couple of things I do not consider to be fictionalization:

--What Licona calls "literary spotlighting." Kindle tells me that "literary spotlight" and cognates occur 36 times in Why Are There Differences in the Gospels. It comes up a lot in the book. But it really isn't particularly literary at all, and it doesn't deserve to be categorized with the above acts of fictionalization. "Spotlighting," despite being made to sound like some sort of technical thing, is really just focusing on one thing, person, etc., in a scene rather than another. So if one author says that there was a man present at a scene who made a certain statement, and it turns out that there were really two men, the author was simply discussing one of the men who was there. That's all that is meant by "spotlighting," and it is so banal and so non-literary that it should not be used to inflate the numbers of "literary devices" in historical works or testimonies.

--Micro-trivial differences of wording. If one author says that Peter was "standing" by the fire and another author says that he was "sitting" by the fire, this wording variation doesn't count as a "literary device," and frankly, shouldn't even be mentioned. One of the most frustrating aspects of Licona's book is that he fills page after page with this sort of micro-trivia. It is not that he is claiming that all of these, or even many of them, constitute contradictions, but he does treat them as worth mentioning and as "changes" that the authors allegedly made to their "sources" as opposed (apparently) to their just naturally telling a story as a normal person does (perhaps even an eyewitness) in their own words. This habit of Licona's makes such micro-trivia sound like deliberate redaction, and it further increases the impression that, say, Matthew didn't actually witness any of the events he relates and tell them naturally as he remembers them. To Licona's credit, he tends to leave out this sort of itty-bitty trivia in his lectures (see here and here), which for that reason are better representations of his approach than the book itself. See two of my earlier posts critiquing Licona's talks here and here.

--Some degree of approximation or paraphrasing in telling what people said, as long as the author has good reason to believe that this really is approximately what the person said at that time, is not fictionalization as I'm using that term.

With my use of the term "fictionalizing literary device" clarified, on to the chart. The flowchart is meant to show how difficult it should be for a reasonable person to conclude that there is a fictionalizing literary device in a text where the author provides no clue that such a device is being used. In a post last year I stressed that a characteristic of the "devices" that Licona and others claim to find in Plutarch and the gospels is that there are no such clues in the text. This is important to remember. The authors do not give you a "heads-up." Instead they "write as if" things are a certain way. This creates all sorts of empirical difficulties with drawing this conclusion. The flowchart shows that there are many hoops one has to jump through before reaching the conclusion that something so complex is going on.

Most of the claimed instances of such "devices" given in New Testament scholarship and (in Licona's book) concerning Plutarch and other ancient authors don't even make it past the first step: Can the accounts be harmonized without undue strain by traditional methods?

Naturally, each person's concept of "undue strain" will be slightly different, so (as they say), your mileage may vary. But New Testament scholars are the most sensitive of plants when it comes to the idea that a harmonization is strained. They pretty much consider the most obvious ideas to be strained. They start with a wooden reading of the text, often a strong over-reading, and then they proceed to create some sort of "tension" between that text and another text, and they then resist the sensible suggestion that one needn't read the texts as saying that at all. On other occasions there is some degree of prima facie tension between the accounts, but it can be pretty easily resolved with a little intelligent imagination--something we do all the time, quite rightly, in dealing with witnesses in daily life. All of this is mis-calibrated in certain disciplines. Cases that shouldn't even be thought to require harmonization at all are treated by these scholars as real head-scratchers. Cases that are somewhat more puzzling are automatically treated as irreconcilable differences. I plan to illustrate these points in later posts, and I plan to begin with Plutarch, because I was interested to see how few of the Plutarch examples of supposed "literary devices" even got to first base. I came away from my study with a much higher view of Plutarch's care and accuracy than I'd ever had before!

The second question is an even more difficult hurdle for the proponent of fictionalizing literary devices to get over: Why should we think that the author was deliberately introducing data contrary to fact into his narrative? This is an especially pressing question when the point in question is a matter of detail, timing, the name of a person, etc. There are so many other possibilities, far more probable: The author may have made a good-faith error. The author (if he himself told the story twice, in ways that seemed to imply two different sets of facts) may have obtained additional information in the meanwhile. Nor does the fact that the accounts weren't published very far apart refute this suggestion. One can obtain new information in a single day! The author may have had information he was justified in considering reliable that was slightly different from the information that another author had, which the other author was justified in considering reliable. Two people may have remembered things slightly differently, if they were both present when an event happened. An author may have simply lacked information and written in a way (true as far as it went) that reflected this lack of information. (E.g. When Luke 2:39 says that Mary and Joseph returned to Nazareth after the purification in the Temple, leaving out the flight to Egypt, this may simply mean that Luke hadn't been told about the flight to Egypt.) And so on through near-infinite variations on the many ways that people get information and try to relate it truthfully. Remember too that we're talking here about secular documents as well as the New Testament. Even if you shy away from saying that John made some minor error (but I don't think you should), why shy away from saying that Tacitus did so? And I would add that attributing deliberate fictionalization to John is a far heavier and more serious matter than attributing a trivial error to him, as I have discussed before.

I have now gone through Michael Licona's entire book, and every single example that he gives from Plutarch and the Gospels fails, in my opinion, at either the first or second step. As already mentioned, most fail at the very first step. In a few cases (either biblical or non-biblical) I can see serious difficulties with harmonization, leading to the possibility that there is some inaccurate information in one or the other account involved. But in no case where harmonization seems implausible between accounts does Licona argue persuasively that the author did it on purpose. Indeed, he usually just asserts it. He hardly even seems to realize that he needs to argue at this step in the chain of reasoning, that it is far more complex to assert that Plutarch, Tacitus, or John the evangelist deliberately inserted non-factual material than to conclude that he just got it a bit wrong at some point or just remembered it differently from someone else or from his own earlier version. One is claiming to be getting inside the author's mind and to be able to tell that he did this on purpose--a strong claim. Therefore, there should be some pretty robust argument that the fictionalization was deliberate. This is so obvious an epistemic point that I find it a little astonishing that it needs to be made explicitly, but apparently it does. Nor is Licona the only scholar to have this problem. In fact, he seems to be picking it up from others.

Burridge does slightly better (Four Gospels, One Jesus, pp. 169-170) when he argues that Tacitus probably invented the speech including the famous line "solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant" and attributed it to the Scottish chieftain Calgacus, who (if nothing else) almost certainly didn't speak in flowing Latin parallelism. Tacitus presumably knew that as well as we do and therefore probably knew that he was including an invented speech. If he wrote the speech himself, he of course knew that he invented it himself. And we know that Polybius complains about people who invented speeches in historical books, so it was something that was done, though it was (as Polybius's own complaint shows) not universally accepted as a harmless device. But as I pointed out in an earlier thread, Tacitus is known to be quite accurate in his narratives, which shows that we shouldn't jump to conclusions about an author's "license to invent" across the board even within his own writings, even if we decide that in some given, circumscribed aspect of his writings (such as speeches) he probably did invent.

But Licona's examples concern names, places, events, and (perhaps most often) chronology. These are the types of facts that one could easily report (or imply) without realizing that one was not getting them quite correct or that one was giving one's readers an incorrect impression. That such simple hypotheses receive such short shrift in these disciplines is a sign that something is very wrong. One is tempted repeatedly to ask why in the world a scholar would jump to the conclusion of deliberate fictionalization when so many more common options exist.

If one manages to get this far with a given example, another problem looms, one which I hinted at in my previous post. If we (somehow) know that the author deliberately inserted false information, why not just call him a liar rather than assert that he's using a "literary device"? In fact, even finding quite a number of examples of "fake news" in the ancient world would hardly suffice to justify the conclusion that these were "literary devices" and accepted as such by audiences. Would that be the correct conclusion in our own culture, if a later historian found numerous cases in which news sources fudged their facts, reported with extreme carelessness from unreliable sources (and hence got it wrong), or outright made stuff up? Of course not. The correct conclusion is that these news outlets, which should care about truth and whose stories are supposed to be taken as factual, are insufficiently concerned with getting it right. That they are liars, or play fast and loose. That they are propagandists. These are all well-known phenomena in human experience. It is far more probable, if (say) Josephus at some point really fudged his facts, that he did it as a sinful man than as a literary lion.

Note, too, that the fact that some people, even many people, know that one does this sort of thing still doesn't make it a "literary device." Maybe the common man on whose emotions one intended to play does not realize that it is made up, but some other people have tumbled to the truth. Cynicism doesn't create fancy literary devices. Even if I realize that the Huffington Post is sometimes unreliable in ideologically freighted areas, it doesn't follow that they are doing something perfectly licit and "literary" when they bend the truth. It just means that I am justifiedly cynical.

Once again, when scholars are alleging "literary devices" and even making explicit statements about what readers would have expected, they rarely seem to bother to argue for this thesis beyond producing the examples themselves. The simple question never gets asked: Even if this author did this on purpose, why should I not think he just liked to make stuff up?

A more lighthearted example here will help to illustrate. All my life I have greatly enjoyed the memoirs of the late Gerald Durrell, a naturalist who traveled all over the world collecting animals for zoos. In his childhood, Durrell lived on the island of Corfu for five years, and his beautifully written (and hilarious) books about that time are among those I've re-read so often that I nearly have them memorized. The most famous is My Family and Other Animals, and if you've never read it and need an enjoyable and relaxing book for your next vacation, I cannot recommend it too highly. If you like it, try the sequel, Birds, Beasts, and Relatives. Don't look for deep insights. Just amusement of a mid-20th-century British variety that treats drunkenness, homosexuality, and the incompetence and melodramatic temperaments of Greek peasants as comedy fodder. I've read that Durrell said that his childhood in Corfu unwound before his eyes like a film when he went to write about it, and his descriptions of the island are incredibly vivid.

But later, as I got to thinking about it, I came to have my doubts about the truth of some of the anecdotes. It wasn't just that I assumed that Durrell constructed dialogue he didn't remember clearly, for basically factual scenes, to make the dialogue sound novelistic, detailed, and seamless. That might really count as a 20th-century "literary device" that an audience fully expects. (No, I don't think there's any reason to believe it was a 1st-century literary device, much less that the authors of the Gospels engaged in it.) It was rather that I started thinking that some of the stories he tells are too fantastic to be true. Also, I read a few scattered stories about Corfu and about his family that Durrell wrote later in life, and those read like pastiches of the earlier stories. This caused me to put a bit of a question mark over the earlier stories as well. Did he really have a hunch-backed tutor who lived in a fantasy world where he repeatedly saved damsels in distress? Could that same tutor really have had an elderly mother with long, undying red hair who believed that she could hear flowers talk? Did the Belgian consul in Corfu really shoot starving, feral cats from the window of his house with an air rifle (as a form of euthanasia) while trying to teach French to young Gerry? Did the Durrells really use rare postage stamps to bribe a philatelist Corfiote judge to decide a minor court case in their favor? And so forth.

Now, maybe all of that really happened. Truth, they say, is stranger than fiction.

But let's suppose that my suspicions are correct and that some, at least, of those incidents are made up. Is that a "literary device"? Heck, no. Nothing so high-falutin'. It would just mean that Durrell was a mischievous guy, a great raconteur, that he made his living and funded his animal collecting trips by writing books and was very good at it, and that he didn't have qualms of conscience about mixing fiction with fact to make a better story. It doesn't matter all that much if he did so, but the reason that it doesn't matter has precisely zilch to do with "literary devices." Instead, it has to do with the intrinsic lightness of the subject matter. If Durrell were asking me to commit my life to a religion, I would be rightly indignant at his fictionalizing in the service of that goal.

And then there is the final node. I admit that the distinction between this node and the previous one is not sharp. I included the final node for the sake of completeness. How plausible is it that the author himself believed that he was using an understood "literary device" but that, as it turned out, most of the members of his intended audience had no way of knowing about such a device, unbeknownst to him? But I suppose one can imagine something like this, using the previous example: Suppose that Durrell inserted fictional tales among his true memoirs, and suppose that he thought to himself, "I bet that everybody understands that this is the sort of thing that an author like me does. Surely people will realize that the fantasizing, hunchbacked tutor is too weird to be true." In that case, he was, as it were, trying to use an agreed-upon literary device but being too subtle about it, and for most people he probably failed. I don't think I'm atypical in that regard. I certainly took all the stories as intended to be factual for many years.

The assertion that Licona et. al. blithely make about ancient audiences and ancient peoples is incredibly hard to support. I really don't know how they think they can support it for such a wide array of fictionalizing "devices." They might, might be able to support it for some isolated type of thing in a work--speeches, for example, that (upon examination) are "too good to be true." But if so they'd have to show it on a case-by-case basis, and I don't think they do show it even for, say, the speeches in Acts. (Which, by the way, appear to be remarkably accurate even if somewhat paraphrased.) If this could be done for some isolated aspect of a work, it would be similar to showing that most 21st-century American and British readers realize that a person who writes his memoirs will often change the names of various people involved so as to protect their privacy. Audiences realize this in part because books will occasionally even say this in an introduction, but even when they don't, no one is really surprised. For example, I was not at all surprised to discover that "James Herriot," the Yorkshire vet whose memoirs I have always enjoyed, was really named Alf White and that his partners, who figure so prominently in his stories, had different names as well.

But these are isolated types of things, and one can argue for them carefully on a case-by-case basis. I have found no such persuasive argument for the general recognition, by audiences, of the range of "devices" Licona discusses. Licona presents a reference to one brief statement in the work of Lucian of Samosata which may endorse the invention of speeches by historical writers. Lucian says that when a writer of history introduces a speech, he has "the counsel's right of showing [his] eloquence." But Lucian is just one guy, and even the invention of speeches (much less the other "devices"), even in the pagan world (much less by the authors of the New Testament), was not universally accepted. One statement about speeches from Lucian is a thin reed on which to rest the weight of Licona's sweeping claims about the ancient world and a whole zoo of fictionalizing devices.

Besides presenting his Plutarch examples (some of which I'll discuss in a later post) and more or less saying, "Behold!" the longest attempt Licona makes at an argument for the widespread acceptance of fictionalizing literary devices is his deeply flawed discussion of "compositional textbooks." There are many problems with that, beginning with the fact that we have no reason to believe that any of the Gospel authors with the possible exception of Luke would ever have laid eyes on, say, Theon's Progymnasmata. Moreover, it doesn't appear that such "textbooks" were teaching about a societally understood set of conventions for fictionalizing history but rather merely giving writing exercises and trying to teach how to write well, whether the content is fiction or fact. As I discussed in this post, writing advice/exercises and a treatise on fictionalizing history are completely different things--a point Licona doesn't seem fully to grasp. I could say more at length about the confused use Licona makes of Theon, but Theon himself warns against long digressions, so I'll leave it at that for now.

Similarly, Licona quotes (twice) a passage from Lucian about how the historian should try to make his work flow gracefully. Licona then interprets this to mean that Lucian was teaching that it's okay for historians explicitly to change the time when things happened so as to make the series of events flow more gracefully from one thing to another! But Lucian says nothing of the kind in the passage Licona relies on. The passage is merely a more or less vague discussion of writing in a way that is "smooth" and "connected" and in which the various topics fit together like links in a chain. A quotation from Quintilian, used by Licona in a similar way, is similarly vague and also does not support Licona's conclusion (pp. 89-90). I note, again, that it is perfectly possible to narrate events more topically than chronologically while not even implying that one is narrating chronologically, much less implying that one is narrating a different chronology from some other document or from the way things actually happened. Hence, injunctions that might support a somewhat topically arranged narrative order do not go any distance toward supporting changing the chronology of events, which is a completely different matter.

It is therefore worth questioning whether the fictionalizing "literary devices" that Licona lists (transferal, displacement, etc.) even existed in any meaningful sense--a question that makes the last two nodes of the flowchart particularly pressing.

This is another way in which the argument doesn't even get off the ground. Some people to whom I have spoken about these issues seem to think that it's established that there "were these literary devices at the time" and that, then, the only question is whether the Gospel authors would have used them. Certainly the second question needs to be asked! Even if one runs the gauntlet of the entire flowchart for some particular passage in Author A, one is by no means entitled to populate the entire ancient world with authors of this kind, much less assume that some particular other author was also inclined to use such a "device." But I would press the skepticism further, questioning whether "transferal," "displacement," and "conflation" qua literary devices were even hanging around in the corporate mind of society to be used at the time of the Gospel authors. And so much the less for more radical "devices" such as "crafting" the entire incident of Doubting Thomas, suggested by Licona (p. 178). So far, I haven't seen anything that convinces me that such abstract entities existed. The flowchart helps to explain why.

Comments (112)

Your use of the words "fictional" and "fictionalizing" was a little bit confusing to me. Sometimes you use them contrary to their usual meanings.

The difference between historiography and fiction is a lot simpler than people might guess. It's one-dimensional, defined simply by truth-claim: a text is historiographic if it claims to be a true account and is fictional if it doesn't claim that. (Meir Sternberg shows this elegantly in his Poetics of Biblical Narrative.) Of course, truth-claim depends on conventions and on the expectations of the particular readership.

So in particular, "fictional" does not mean false. Something could be fictional and factually true, or historiographic and factually false.

Similarly with "literary device": Literary devices are often used in historiography—writing that makes a truth-claim—as well as in fiction. So re your question, "why not just call him a liar rather than assert that he's using a 'literary device'?", you're right that "literary device" is just a smokescreen. The question is simply whether the text is claiming to tell the truth.

Posted by Aaron Gross | September 21, 2017 1:05 PM

Well, I'm not trying to run counter to some established usage of the term "fictionalizing." But I think I define it pretty clearly. I'm sorry if my usage seems strange to you, but what *I* mean by "fictionalizing" is that one is writing what either is non-factual or what one has no reason to believe is factual. However, if one's work is putatively historical, one may be *presenting* that material as fact. So this is different from your use of "fictional." As I'm using the concept of a "fictionalizing" author, John would be "fictionalizing" if he "crafted" the Doubting Thomas scenario contrary to fact (it didn't happen), even if he presented it as fact. Matthew would be "fictionalizing" if he invented a second demoniac in a story when he knew there was only one (or when, as far as he knew, there was only one). John would be fictionalizing if he definitely presented Jesus as cleansing the Temple early in his ministry when in fact Jesus never did cleanse the Temple early in his ministry. And I would call these "fictionalizing" even though they present these things as having actually happened. Indeed, that's what would make it problematic.

Posted by Lydia | September 21, 2017 1:15 PM

I havent read Licona's book, but its a shame he is going down that alley. He has been very good on the resurrection of Jesus, but once you start effectively saying the Gospel authors made some stuff up but presented them as real events or facts to make a point, I think you're on shaky ground. I doubt the first readers of the Gospels would have understood that is how they should be reading the accounts. The question is of course - if some details are made up, or the words of one person have been placed in the mouth of another etc, how does one know what really happened and what didnt? Luke, in his prologue, specifically says he was writing facts.

It is these sorts of arguments that quite rightly just confirm the atheist position - we cant know what to believe as 'truth' in the Bible, so better dump the whole lot!

Posted by PC1 | September 22, 2017 10:09 AM

There were two different men who dropped atom bombs on Japan, Tippet (Little Boy) and Sweeney (Fat Man). Sweeney wrote his memoire and Tippet wrote his own, with an additional chapter, essentially, calling Sweeney a liar for whitewashing why Nagasaki was bombed instead of the primary target, Kokura.

Likewise, during WWII the two physicists, Niels Bohr and Wolfgang Heisenberg had a conversation in the woods outside of Bohr's cabin that so infuriated Bohr that he, essentially, threw Heisenberg out of the house (the basis for the play, Copenhagen). Bohr and Heisenberg have radically different accounts.

My point is that many people (at least 5000 at one time) saw Jesus, so the details of his public ministry were no secret. If the Gospels were at all fictionalized, you can darn well bet there would have been a written record of people setting the record straight, but there is not even a peep from anyone. There were enough educated Greeks and Romans that something would have survived. In fact, no counter-narratives exist. Such stories were passed down by word of mouth (such as the Roman claim that Jesus's body was stolen), but they did no survive long and were not regarded as being worth of being recorded in writing by non-Christians.

If the Gospels were bring fictionalized, you can bet the Jews would have been all over the text or at least challenging the oral record before the Diaspora.

How does Licona explain this?

The Chicken

Posted by The Masked Chicken | September 22, 2017 10:17 AM

Chicken, if I were arguing Licona's side (which of course I'm not) I would guess he'd say a) the fictionalized details in question are mostly too peripheral for it to be worth someone's while to dispute them in an explicit way in order to set the record straight, b) the very discrepancies (as he views it) between/among the Gospel accounts *are* the contrary versions, so we really *do* have differing accounts (just not as dramatic as the ones you mention), and that's why he's making these conjectures about literary devices.

E.g. He'd presumably say that John's account of the cleansing of the Temple or of the day of the crucifixion *is* a contrary account to that in the synoptic Gospels. But he would argue that John doesn't call the synoptics liars, nor did anyone else write at the time calling John a liar, because John's readers understood that he was allowed (literarily) to make alterations to such things as what day Jesus died or when Jesus cleansed the Temple, so nobody was going to make a fuss about it.

The view is that there is this "core" that everybody wanted to remain stable (e.g., Jesus died and rose again), and that a lot of other things are, as it were, literarily negotiable, and people didn't mind if they were tweaked in a fictional way.

Perhaps the most extreme example of this is Licona's theory (which isn't in his book but was given in an on-line debate with Bart Ehrman) that all of the non-overlapping material on Jesus' infancy in Luke and Matthew might be a so-called "midrash"--i.e., made up. But they agree that Jesus was born of a virgin, so what they agree on is the "core." This would mean, presumably, that the wise men, the shepherds, the slaughter of the innocent, and the flight to Egypt are all so-called "midrash," but nobody minded because *somehow* people had ESP (okay, I'm getting a little sarcastic) to recognize this "genre," and the core (the virgin birth) was retained in both accounts. So nobody bothered to write a disputing account calling out Luke and Matthew for their "midrashic" additions. I shd. add here that N.T. Wright has said some very strong things about the abuse of the term "midrash" in exactly the way that Licona is using it for this conjecture about the infancy narratives.

It's at that point that this stops sounding particularly peripheral! Those are whole incidents in the infancy of Jesus.

I suppose I can see why someone wouldn't write separately in the 1st century to clear up whether there were two demoniacs or one or whether the centurion with a sick servant came personally to Jesus or sent his servants. Those might seem not worth "calling out" a gospel author who (in some other person's opinion) didn't get it quite right. But when we get to "midrashing" over half of the infancy narratives, the concept of a "core" vs. a "peripheral detail" wears rather thin.

Posted by Lydia | September 22, 2017 10:48 AM

Hello Dr. McGrew,

Thank you for your work. Do you perceive that the appeal to ubiquitous contemporaneous literary devices can serve for some as a backstop to loss of "faith", in the same way as unexamined insistence on anachronistic inerrancy? Is there a false dichotomy here? Also, do you think that once a scholar starts specializing in a certain aspect of literary criticism, he or she is prone to start seeing those devices everywhere, as an answer to every difficulty in the source? To what degree do we honor the source, especially in conversation with unbelievers, before it seems special pleading to divine inspiration, or the dreaded "mentally gymnastic harmonizing?"

I appreciate your insight.

Posted by Kevin Wells | September 22, 2017 11:59 AM

It is definitely supposed to be a backstop to "inerrancy" itself, though a redefined concept. I've had people tell me *explicitly* that they feel they have to take Licona's ideas seriously because it is a way to retain the idea that the Bible gets nothing wrong in what it *affirms*. Basically, you just radically fuzzify the question of whether John was *affirming* that Jesus did this on a certain day, because if it's a "literary device," then none of that counts as "affirming." Therefore, if John *changed* the day, he was sort-of-affirming-it-but-sort-of-not-affirming-it. He made it look like a different day, yes, and he did that on purpose, yes, but because it was a "literary device" of the time, nobody took any of that detail as *serious historical affirmation* anyway, so it doesn't count as being incorrect in what he "affirms."

It's an *incredibly* Pyrrhic victory for "inerrancy," as Norm Geisler rightly saw. One retains the ability to *say* that the gospels are never wrong in what they affirm only by (more or less) saying that they don't really affirm any of the details of their narratives! However realistic they make them appear. Or, if we accept the "midrash" idea for the infancy narratives or John's "crafting" the whole Doubting Thomas scenario, I guess John wasn't really "affirming" that either. Sort of like if I say, "Once upon a time" and tell a fairy tale, I'm not affirming that it really happened. Only unfortunately John doesn't have any cue words like, "Once upon a time!"

So, yes, people use this as a backstop for inerrancy. Let's radically redefine our concept of what the gospels are affirming, and then we can say they never get anything wrong that they "affirm." It's crazy, in my opinion, but it's astonishing how many people are tempted to go that route.

Whoa, hold on. Remember, I think these guys are over-reading *Plutarch* and wrongly attributing fictionalizing literary devices to him, and I don't think Plutarch was divinely inspired!! The flowchart in the main post is for *any* sources. I don't try to harmonize because I'm a "believer" or because I'm pious or anything. I try to harmonize because it's good historical practice.

When it is mental gymnastics and when it isn't just depends on the individual example, and of course people will disagree. But again and again and again, both for Plutarch and the gospels, Licona is ignoring very *reasonable* harmonizations. These scholars don't seem to know a reasonable from an unreasonable harmonization. It's very sad.

And in any event, please, please remember: There are several nodes to the flowchart *even if* you just can't come up with anything you regard as a plausible harmonization. If you think two accounts can't be well harmonized, it would virtually always (always so far in my experience) be far more reasonable to think that someone made a mistake than to think he's engaging in a "literary device."

Yes, happens all the time. Craig Blomberg even complains about this to Licona in a round table, quoted in an earlier thread. That Blomberg thinks Licona is seeing these devices under every rock. If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail, etc. I think too that the problem arises from the intrinsically empirically unverifiable nature of these devices. *Since* there is no indication in the text that they are taking place, and *since* we can always say one is there when we don't like any of the available harmonizations, and *since* the motivations alleged for doing these devices are allowed to be *incredibly* thin and/or vague, then they can be multiplied ad infinitum.

At one place in the book (I am not making this up) Licona literally suggests that Luke may have altered the chronological order of events in order to "change things up slightly"!! That's an exact quote. pp. 166-167. Change things up slightly. My jaw dropped when I read that. That's all it takes. That's all Luke had to have. Just a desire to "change things up slightly." On pp. 182-183 he literally says that most often the authors' motives for making these changes are just "to follow the literary conventions of their day." In other words, they changed these things just because! Just because they could, and because that was a "literary convention of the day." Not even for any clear theological or other motive.

When your standards are that low, even for the putative motives for changing chronology and other details--yeah, you're going to "see" these "devices" pretty frequently.

Posted by Lydia | September 22, 2017 12:58 PM

I just went back and did a quick review of Plutarch's life and works. I am a bit puzzled. Does Licona believe or not believe that becoming a Christian makes a difference in one's life? How can one possibly compare the writing style of Plutarch, a pagan and a priest of Delphi, by all accounts, with the writings styles of the Gospel writers? He might as well be comparing the writing styles of New Age Shirley McClaine (sp?) to Mother Teresa. In order to make a fair comparison, he would have to compare Christian writing techniques against Christian writing techniques of the period. In modern terms, if one looks over the corpus of Christian romance novels, one sees certain common tropes that simply do not exist in secular romance novels and vice-versa. Yes, there may be a certain overlap of techniques, but how does one decide what those are based on a very limited sampling?

Plutach, in his Parallel Lives, for example, seems to have grasp at straws to set up his parallels in certain cases. He used many literary embellishments. What gives Licona the right to think that the Gospel writers did the same thing? It looks to me as if he does not consider the New Testament to be Divinely inspired, except in the most general way.

Christians think differently than pagans. I do not see how one can make comparisons, especially given the different notions of what constitutes sin. While Plutarch many not have thought rearranging text to be a big deal, what evidence does he have that John did not?

In musical terms, since that is where I have some relevant expertise, C.P.E. Bach and J. C. Bach were not only contemporaries, but brothers and, yet, their compositional styles could not be different. They each have similar styles to other composers of the period, so one can establish stylistic groupings of those different schools of composition as such, but just because the two composers esisted at the same time, one cannot, thereby conclude that they used similar techniques.

When one becomes a Christian, certain behaviors change. What does that mean in terms of writing style? I suppose that that is at the heart of the problem.

The Chicken

Posted by The Masked Chicken | September 22, 2017 5:34 PM

I strongly agree with this, and I think it has to be kept in mind that we shouldn't make huge generalizations about "the ancient world" as if it were monolithic. (This is a bad habit of another author I have critiqued, John H. Walton. He takes it to an extreme, treating even the "ancient world" of the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the pagans, Jews, and Christians as very similar in contrast to...the Modern World. This is incredibly poor historically. And anachronistic, as well.)

However, I'm looking forward to showing how over-wrought these ideas are with respect to Plutarch as well--at least as regards the examples Licona gives in his book. I didn't find a single place where I thought he made a good case that Plutarch *deliberately* changed a fact from true to false. It wasn't that I was closed to finding it, though I would still have doubted that it was a "literary device" as opposed to ordinary deception. (See flowchart.) But we didn't even get that far. It was an interesting thing to come away thinking better of Plutarch's literal accuracy than I ever did before. Surely not what Licona intended to be the result of studying his book! Maybe there are such deliberate fabrications on the part of Plutarch out there. I would treat them with a shrug, if so. But I wasn't inclined to think that Licona showed any convincing examples.

Posted by Lydia | September 22, 2017 7:10 PM

I just want to mention one qualifier we need to keep in mind with respect to this aspect of a definition of "fictionalizing": There is at least potentially a matter of degree. For example, in "political speech" in these teen years of the 21st century America, a certain amount of exaggeration, or embroidery, is at least tolerated, even if not simply "accepted". A man who claims he "helped create the Internet," if he was one of 13 co-sponsors on a bill that provided funding fairly early for some elements of what eventually became the Internet will be both laughed at because he inflated his contribution, and tolerated because is not entirely wrong, either. A man who accuses his opponent of being "soft on crime" because he did not vote to increase mandatory sentences is engaging not so much in lying as in "over-stating the case", which is more or less tolerated. Sort of. To a degree, though not simply. That is, we don't hang the politician, or charge him libel, nor do we automatically say "that's it, I can't vote for him because he embroidered the truth here in this tangential matter." On the other hand, we also don't completely shrug it off as if it were good and worthy behavior, as if that kind of embroidery is "the upright and wholesome way to go about being elected" (Trump supporters excepted). We don't treat it COMPLETELY as "a literary device that gets to a deeper truth better than the bare facts would have done, and is therefore preferred over a 'just the facts' account that fails to get the 'underlying truth'." So, there is a difference between toleration and full acceptance.

A lot of this is nuance, a matter of difficult-to-enunciate distinctions that people keep in mind without stating "for the record".

So, the problem with assessing an earlier culture's literature for this matter is in being able to say whether a particular sort of stretching of the truth fell into "tolerated" versus "accepted device", because the kind of evidence that would have distinguished the one from the other is not necessarily easy to locate or identify, especially at a remove of many centuries. Indeed, even if someone (contemporaneously) were to have written explicitly an essay (or, more likely, a polemic) that touched on the distinction in regard to specific cases and examples, we could still have the situation where THAT WRITER's own personal sense of the boundaries were not necessarily quite in tune with the general run of the mill perceptions, or his specific examples might have been controversial even in his own milieu. How would we ever know? Imagine someone a thousand years from now trying to discern whether, in our culture, Trump's comments that have only a glancing relation to truth are "accepted" versus "tolerated".

There is, also, the problem that "the milieu" can be incredibly narrow. What is accepted in my hangout at the gym on 7th Street, and what is accepted in the soiree on Main St., can be quite diverse. What is accepted in 2017 may not have been acceptable in 1997, or 1977. What is accepted in practical politics (campaigns) surely is different from what is accepted in physics, math, or even a political science treatise. These all make it more difficult to be sure of what is tolerated versus accepted.

The problem for Licona and his ilk is that the epistomological presumption must be in opposition to "it was an accepted fictionalization" about any specific example. So they have this enormous burden of proof to overcome, not only in identifying the "genre" of writing, but also of identifying the "accepted standards" for that particular genre WITHIN the milieu in which the author was writing, which might be different from the standards 200 miles and 20 years removed.

My personal take is that the "fictionalizing" theorists have completely mis-identified the genre. Maybe in a verbal account, maybe some of those disciples might have engaged in some exaggerating or embroidering. But these apostles - especially (among the writers,) Matthew - were nothing like an "artiste" in their earlier life. Matthew may have been little more than a thug who was good at sums. When they set out to put those stories in writing, they would have been far more careful in what they put down. And they would not have been part of the milieu of Livy and Ovid and Plutarch who were writing of mundane matters to other scholars. These accounts were read aloud in the assemblies, not to literary folk, but to fishermen and tent makers. Different milieu altogether from the soiree on Main St.

Secondly, the fundamental thrust of the writing, (as with their verbal efforts) was to convince people of astounding truths: God became man! Then He died for your sins and mine! There is, in my opinion, a FUNDAMENTAL incompatibility between an account that knowingly and intentionally rests on an honest account of miracles as convincing evidence of these claims, and then using any kind of fictionalizing in the same account. Any kind at all. Any use of a fictionalizing device at all leads the reader to the possibility that the miracle accounts were fictionalizing devices, and that unwinds the motive for belief to begin with. (This is all the more so when, as Licona says, there was no "pointer" for the parts that were fictionalized versus the parts that were stone cold factual.) It is an unavoidable consequence of using fictionalizing of any sort.

The Device defeats the whole purpose.

But even if it didn't, you still have to run the gamut of the flowchart filters Lydia laid out for us.

Posted by Tony | September 23, 2017 10:55 AM

By the way: there is adequate proof for my claim that

Any use of a fictionalizing device at all leads the reader to the possibility that the miracle accounts were fictionalizing devices, and that unwinds the motive for belief to begin with.

This is exactly what has happened in colleges and universities for the last 100 years, all across the US and Europe. The students have walked away from Christianity because it lacks any motive of belief, when you look at the accounts as harboring intentional fictionalizing.

That a few theorists manage to withhold from dis-belief even while believing in fictionalizing is an example of "believing 6 impossible things before breakfast". If, that is, you can call their modus operandi "belief", which in some cases is problematic.

Posted by Tony | September 23, 2017 11:09 AM

Lydia:

I have a problem with your step 1. The flowchart gives the impression that the availability of a mildly strained, but not "unduly" strained harmonization is sufficient to conclude that there was no fictionalizing literary devise (FLD). I suppose your main point is that, in that event, there is no BASIS for the claim that an FLD is present. But even that depends on how plausible we think it (prior to this investigation of a particular text) that the permissibility of FLDs may have been in the ethos for Hellenistic historians. Your approach takes that to be a priori highly improbably so that some heavy burden of proof must be met before concluding that we have an instance of an FLD. I, being more open to the possibility from the start, when I see that accounts are harmonizable only with some strain, ask myself whether the FLD hypothesis is a better explanation than the harmonization. If it turns out (after going through the rest of the flowchart) that the best explanation of a discrepancy is provided by the FLD hypotheis, then to that extent this text is evidence for FLDs. Admittedly, to the extent that the strain of the harmonization is not very great, the presence of a possible harmonization makes this only weak evidence. All I'm asking for is an even handed evaluation of the evidence.

Secondly, in the case of the Bible, I also have a problem with the rest of the flowchart. I think it's a plain fact that the whole church throughout history has taught that the words of the Bible are the very words of God, in a sense that disallows saying "This text, correctly interpreted, says X, and X is false". This may well be called "inerrancy", though I have no very profound attachment to that word, and if it be taken to include an affirmation of "common-sense historicity" (the principle that where informed common-sense would interpret a text as affirming historicity it should be so interpreted) then I simply note that the whole church throughout history has not taught that. Indeed I have found, just recently, in Origin and Augustine statements that seem to strongly indicate they rejected it.

Since the divinity of scripture is something I know to be true, I can't just leave it out of consideration when attempting to discover further truth. And since the divinity of scripture disallows me from saying either that the author mistakenly or deliberately asserted something false (or that he intended to describe non-assertorically a detail when facts about his linguistic community entail that his statement actually does have assertoric force) I end up with only two viable options: harmonization or denial of assertoric historicity. I think I mentioned way back when this topic first came up on this blog that I have some problems with Licona's particular way of doing this, and I don't care for his term "literary device" (or your term, "fictionalize"), but I'll leave that aside for now.

If you mean propagandistic fictionalization ("fake news") then that's a serious matter, but if we are talking about FLDs then by definition the credibility of the author is not undermined, and the divinity of scripture is not in any way put at hazard. By contrast, it at least presents a real difficulty for the divinity of scripture to suggest that the text is in error in what it affirms (even if you are right in believing that the difficulty can resolved, somehow, and the divinity of scripture can survive the abandonment of inerrancy). You want to say that inerrancy is put at hazard by FLDs:

But this is the case ONLY IF inerrancy is taken to include a commitment to some kind of common-sense interpretive principle. "Inerrancy-as-Geisler-understood-it" may well be put at hazard in the way you suggest, but that doctrine is not something a traditional-minded Christian needs to feel any great loyalty to. Christians of the past engaged in some wildly ahistorical interpretations, and not only as an addition on top of their commitment to the common-sense historical meaning, though of course that happened too.Is the the heavy seriousness of attributing FLD to John to be found in the fact that if we say that such-and-such detail is not asserted as historical (absent the more acceptable-to-common-sense reasons for saying so), then we can't say that ANY detail is knowable as historical, and thus the whole gospel-record of Christ's life is not knowable as historical, since we can't tell which details are asserted as historical and which aren't?

But that's like saying that we have no idea what Christ actually said because, apart from very few places where, e.g., he's quoted in Aramaic, we have no way to tell which are effectively exact translations of his speech, and which are paraphrases. A paraphrase is a change in detail, an "inaccuracy" in the sense that something is written as a direct quote, as if Jesus said those words, when that's not exactly what "really historically happened." What really happened is that He said different words with approximately the same import. I think the evangelists chose their words with care when paraphrasing Jesus, and this might well include making the connotations of His speech include truths that He enunciated on other occasions. They didn't contradict Jesus' teaching, but they would have represented him as saying, on a particular occasion, something that includes in its meaning (on the level of small detail) what they had no reason to believe he said on that particular occasion. This surely is within what is acceptable to the common-sense interpretive principle. It's worth noting that there isn't a clear line determining exactly how much variation from exactitude is acceptable, on the common-sense principle. Nevertheless, we can know (assuming that principle arguendo) that Jesus said something close to this on that occasion. The departures from accuracy in some details don't undermine a general intention to say what really happened. If this can be true in the realm of reported speech, it can also be true in the realm of reported events. Or it can be the case in the realm of reported speech that more difference from historicity than our common sense allows was allowed to the gospel authors, without undermining the general historical "true-story" character of the gospels. My present point is not that this WAS the case, but that IF it was, that wouldn't be a great heavy problem for the historical character of the gospels. (To be fair to you, Licona's statements about the birth-narratives do go well beyond the level of detail, and his overwillingness to see FLDs where they aren't goes beyond what I'm OK with; and this criticim of yours may have some bite against him in that regard. But as for the present point: merely claiming the presence of an FLD does not undermine the historicity of the gospels tout court.)

The heavy seriousness is found, if anywhere, in the apologetic implications. You have elsewhere mentioned arguments for the historicity of the resurrection that rely on the details of, e.g., Jesus eating fish with his disciples. Now, I think it's possible to prove that Jesus rose from the dead (in the bodily sense in which the church has always understood that) without appealing to anything in the details of the four gospels. Appealing only to the truth of the ancient Hebrew religion, along with uncontroversial facts of history (that Christianity exists, that the Romans destroyed the temple, etc.), we can know that Jesus was the Messiah, and that God raised him from the dead. I don't say this is the BEST way to make the case for Christianity, only that it can be done. So, I don't take it as a deeply serious thing if your preferred way of arguing would be utterly destroyed by the presence of FLDs. But I don't think it is. You yourself note that we are justified in trusting the accuracy of Tacitus, even after we recognize his willingness, on some occasions, to invent a speech.

Still, at worst, the presence of FLDs undermines one sort of apologetic. The presence of error puts at hazard a basic doctrine of Christianity.

Posted by Christopher McCartney | September 23, 2017 5:24 PM

Hi, Christopher. I'm preparing some upcoming talks, so I will be responding to your comment in fits and starts.

Christopher, prior probabilities have to come from somewhere. The argument that Licona and company are making, indeed the *only* argument I know of on this topic, is based in no small part *upon* the examples they claim to find in ancient literature (such as Plutarch). It is in large measure an inductive case. One doesn't just have a free-floating high prior probability of the existence of a device in ancient culture which somehow shifts the burden of proof and makes even the mildest need for harmonization into a case, even a decent-ish case, for the presence of such a device in some text. One usually *starts* with the ancient texts. Even Licona calls his case based only upon Theon & co. a "hunch" and then says that this "hunch" is born out by the *examples* he claims to find in Plutarch, etc. Thus if those examples fail epistemically, one is left without a good reason to believe in the existence of these fictionalizing devices.

Moreover, I have attempted to *answer* the supposed case from other texts, such as Theon or Lucian. For the moment I have decided not to write at length about Theon, but if you think there is a strong case from Theon, perhaps you and I can discuss that in direct e-mail correspondence.

In other words, Licona & co. shouldn't ask us and for the most part (fortunately) don't ask us just to have blind faith in the prevalence of such devices in the corporate ancient mind. If they did ask us just to grant this on the basis of their authority, we shouldn't do it. We should be able to look into it ourselves. But they do try to make a case. I'm answering that case.

Actually, in real life we *often* find that harmonizations take a certain amount of imagination and then turn out to be true. This is simply the nature of testimony and of historical investigation. We may find it surprising that two different people with different names but similar backgrounds drowned in the same river, but it turns out to be true. One witness may say that it looks like the suspect didn't have a car while the other witness says he saw him get into his car, and it turns out Witness 1 simply was seeing out of a particular window where the suspect was running across the parking lot and the car wasn't visible. Craig Keener talks about interviewing people in Africa where it seemed like one witness must be wrong when he spoke of the difficulty of walking across some railroad tracks on a bridge when running away from bad guys (I forget the full story), since railroad tracks aren't that hard to walk across, and then he learned from someone else that the tracks had been damaged by explosives and the fugitives had to walk very carefully across a turned-up narrow *edge* of the track. Such stories can be multiplied indefinitely. This is the very texture of *true* testimony and *true* report--that it isn't tidy.

This is why the hyper-sensitivity of historical critics and biblical literary critics is so pernicious. It positively *teaches* people to despair of the accuracy of the narratives far too easily. It *teaches* scholars not to understand what real testimony is like and to regard the least feeling of (what they regard as) "strain" in harmonization as not-too-awful evidence for a *highly* complex literary explanation. It *teaches* them not to take proper account of the complexity of such explanations. It *teaches* them not to calibrate by recognizing the frequency with which real testimony is untidy and actually fits together in literal reality if all of the reality were known.

I cannot caution you too strongly against going down that path. This is why the burden of proof does lie upon the one arguing for a complex hypothesis such as a literary device, and this is why I worded that first node in the way that I did. Because be it Plutarch or Lydia McGrew telling a story about her day yesterday and someone else telling a story that doesn't fit tidily with Lydia's, it's actually good historical practice to try to harmonize and not to be like the Princess and the Pea when it comes to a feeling of "strain." And certainly not to go haring off after, "Lydia [Plutarch, John] was engaging in a 'literary device' and altering the facts deliberately" without *very* strong evidence. Yes, that is where the burden of proof lies. And a heavy one. I will stick to that.

Posted by Lydia | September 24, 2017 9:29 AM

Christopher, perhaps I got twisted around in there without need, but I can't figure what you are affirming and what you are denying. Is it the term "inerrancy", or is it the concept? Or rather, the "allowing" of saying "This text, correctly interpreted, says X, and X is false."

On the chance that what you meant was that the whole church throughout history, and Origen and Augustine, rejected that

"This text, correctly interpreted, says X, and X is false."

could obtain with respect to passages in the Bible, the parts of the flowchart that consider that the author maybe was mistaken or deliberately lying in order to fool people would remain valid considerations for those non-Christians trying to understand (a) what the texts actually mean, and (b) whether they are historically reliable, just like they have to for any other ancient text.

(Admittedly, that analysis would end up looking very different from one that you or I would engage in. However, it might be interesting to find that both of us AND a secular historian think that "John was not using an FLD in assigning the day of the Crucifixion", if the secular historian arrived at that result thinking that at least in some places, John reported various details incorrectly because he just plain got them wrong.)

Whether there is a high(er) or low(er) prior probability of an FLD in the text would not only depend on whether Hellenistic historians IN GENERAL were considered to be "allowed" to use FLDs, but also whether the gospel writers could be classed as "Hellenistic historians" and whether, within the framework of their own special social milieu and what they were setting out to do, the (possible) allowance of FLDs for "Hellenistic historians" would have applied to them - and in what degree. To me, when you consider who they were writing to and what their purpose was, the notion that FLDs were "allowed" dribbles down to very low probability indeed.

In my own opinion, the notion that there could be an FLD that was NOT separated out from the rest of the text with explicit pointers to the effect that "this is not literal here" (such as "Jesus told this parable...", or something like our modern "Once upon a time...") runs very much along the same lines as the notion that John or Matthew could have engaged in out-and-out lying to fool people.

Posted by Tony | September 24, 2017 12:30 PM

Tony, hear, hear! I couldn't agree more. Also, very good point about how a non-Christian with no commitment to the error-free nature of the Bible could still read and contemplate the reliability of Scripture on its own terms as putatively historical source material. That is so important. And how, for that person, the attribution of fictionalizing "devices" would undermine reliability (in the ordinary sense), but there would be no theological motivation for him to attribute them anyway.

Christopher,

I have a lot more to say in response to your long and interesting comment, but here's one I wanted to get out quickly, even if the rest takes me longer:

A case has to be made that such "devices" as you would prefer to have (rather than attributing an error) actually existed at all. I disagree profoundly with the theological priorities you express in much of your comment. But regardless of which of us is right, you can't (epistemically) get what you want here--which apparently are a set of "allowances" for some degree of what I call "fictionalization," which will then free you from feeling pushed to attribute even a trivial factual error to the gospel authors when you are uncomfortable with harmonizations--unless the case is made *first* for the existence of such allowances in the relevant culture. One might try to do that for Jewish culture, though in fact that isn't where the argument is coming, and I know of no such evidence. Licona and co. are trying to do it for Roman/Greek culture and then transport that to the gospel authors. I think they are failing. But epistemically, that argument has to be made *first* without any theological "help" along the way. That is, if one is going to argue that these sorts of devices were allowed in the minds of the gospel authors' audience because of surrounding culture, one isn't going to be able to argue *that* by saying, "Well, in these other, non-biblical texts, there can't be an error, because I'm theologically committed a priori to believing that God wouldn't have let them make an error." Of course God would have allowed non-biblical authors to make errors, or even to lie outright! So you cannot bring in the theological consideration to reject the rest of the flowchart, because you must argue that the "salvation" you're looking for from these devices (or whatever you want to call them) was even culturally *available*. And you're going to have to do that on independent grounds, aside from theological considerations concerning the gospels, specifically.

Posted by Lydia | September 24, 2017 1:56 PM

I'm get the feeling you see the importance of this yourself, but this type of work that is readily accessible is needed at the moment. Especially dealing with this topic.

2 quick (somewhat irrelevant) questions. 1. Are these talks going to be up on YouTube? 2. I've just ordered the dictionary for Christianity and science where I saw you contributed. I'd love to know what topics they were on? (The book's indexing seems to be an issue among many readers!)

Posted by Callum | September 24, 2017 1:57 PM

I very much agree with this. So many critics find strain when there isn't any. And this is really a huge problem within the discipline. And even when strain exists we absolutely must not overestimate it: we must recognize how often in common life things that seem unlikely turn out to be true.

But by the same token that doesn't remove our capacity for recognizing genuine discrepancies. And the presence of strain in harmonization is an indication of lower probability of its truth (one that is easy to overestimate, but real nonetheless).

Posted by Christopher McCartney | September 24, 2017 2:39 PM

Tony:

Yes.Posted by Christopher McCartney | September 24, 2017 3:32 PM

The ones I'm working on now? Not that I know of. Tomorrow evening I'm doing quite a long Skype presentation on UCs for a small Reasonable Faith group in Tennessee. On Saturday I'm speaking at a church women's conference, giving two talks. I believe one of those talks will be recorded (audio) but I don't know what will be done with the audio.

Topic in Zondervan dictionary: Bayes' Theorem in relation to the philosophy of religion. Relatively brief article, as dictionary articles tend to be.

Posted by Lydia | September 24, 2017 4:14 PM

Prior to making a case one way or the other, I ask: How likely is it that among certain ancient societies the conventions for what was acceptable for a person to put into an honest historical narrative, when he doesn't have reason to believe it actually happened just as he described it, were the same as our conventions? I don't find it terribly unlikely that they were different. But neither do I have (yet) any positive reason for thinking they were different in any particular way. For all I know they could hve been be stricter. (Though a priori it seems less likely for an ancient society without the printed word, and without the institutions that inculcate the modern disciplines involved in careful research into historical fact, to be stricter than our own.)

So, with that nonbiased attitude I look to particulars, and I am looking both at the Biblical apparent discrepancies, and at Hellenistic sources. In the Biblical case, when I come to a particular apparent discrepancy, I CANNOT assume that what at first appears (given conventions I am familiar with) to be affirmed as happening just as described, was probably allowable at the time. I cannot assume that, for I haven't yet made the case for that. But neither do I assume (as you, Tony and Lydia, are doing) that it was almost certainly not allowable. I just don't know. I weigh the plausibility of harmonization against the plausibility of the hypothesis that what appears to be asserted as accurate in detail is actually not thusly asserted, which requires the hypothesis that the conventions were different in some way. I do NOT consider the rest of the flowchart, because I already know the Bible does not contain error.

A single instance where only a somewhat strained harmonization is possible does not give me grounds to draw any really useful conclusion about those conventions, but I make a cumulative case. And in making that case I also look at Hellenistic sources, where I certainly DO have to take into account the rest of the flowchart. Except not in the case of things like Lucien's statement about "the counsel's right of showing [his] eloquence," for that is not an instance of putative creative invention, but an overt endorsement, which bypasses the flowchart entirely.

After I make the case, I then can be more willing to see an apparent discrepancy as not needing harmonization, depending on the character of the discrepancy; and even if I now think it probably doesn't need to be harmonized, I remain genuinely open to the possibility that a harmonization, even a somewhat strained-seeming one might represent the truth of the matter.

Posted by Christopher McCartney | September 24, 2017 4:23 PM

Christopher, you may call it "assume", but it is not an a priori assumption. It is based on at least SOME facts. We have read, of not exhaustively, at least extensively in Hellenistic writings. We have read exhaustively in books of the Bible, which were authored over some thousand years and more, and in several different cultural environments. We know the kinds of things that people claim in their accounts of events, some being clearly mythical, some being rather clearly "just the facts", and some being "memoirs". We know at least a little bit about the manner in which the Gospels (and Epistles) were treated in the early Church...which would have had a certain effect on the attitude of the later gospel writers in setting about their task. We know something of the lives of the apostles and their closest disciples, (many of them persecuted and martyred). Without necessarily being able to give absolutely complete analysis of all those factors in detail, but still based on them, I judge that the "prior probability" of the gospel writers thinking of and treating their task as "in the same nature" as those Hellenistic writings that had known and accepted FLDs is very low.

That's on an "assumption" that there really is such a thing (in the Hellenistic historical writings) as "known and accepted FDLs" as such.

If we ask the question whether there was such a thing to begin with (and force Licona and co to justify the thesis properly), ON THAT account, I think we also start with a pretty low "prior probability", i.e. an assumption against.

Here is why I think that: the proposed nature of these FDLs is that they are (all at the same time), (a) known to the author as being counter-factual), (b) have no distinguishing marks in the text separating them out from the simply true parts, and (c) readily accepted by the readership as an approved literary behavior. But the very nature of an "historical account" is, in essence, one of recounting things that happened - i.e. real events. And I think it is universal in humans to want their readers to believe in an account given, when it REALLY IS a factual account just as I saw and heard it. That is, the author naturally wants his readers to believe him when he describes what he saw.

Now, if a man puts down what he saw in 90% of the account, and added 10% non-factual claims, he could do so for one of several reasons. He might be a fraud, and be using the WHOLE account to "get something" from the reader". (Even if what he gets is fame and prestige.) In that case, he wants and hopes the reader believes the WHOLE account, not just 90%.

However, if people found out - after first thinking that X part was true - that X part was false, they will refuse to credit the REST of the account as being factual also, and he will fail to achieve his purpose. So, their coming to the conclusion that "part X is false" does not fall in with his purposes of fraud. His intent is that they accept all of it as fact.

Suppose, on the other hand, he writes 90% "just as it happened", and 10% as filler that is added "for other purposes" (not to fool people), and he really doesn't mind that they don't believe in the 10%. However, in any group of 100 people, different parts are considered to be the "made up" parts by different people, and as a net result, 95% of the people walk away quite wrong about what they think actually happened. In particular, what they might get quite wrong is the internal "sense" of why what happened really happened, because they will attribute different parts of what goes into the "why" as being made up. The net result will be that he tells one story, but what 100 people believe is 100 different stories, none quite true.

That is to say, in having "made up" portions, and in having absolutely no pointers that distinguish them, he is effectively guaranteeing that almost nobody gets "the story" and "the point" the way he intends them, because everybody is busy deciding on the basis of THEIR OWN PERSONAL PREJUDICES which parts are true and which are made up.

Effectively, there is no point to telling a history with accepted FLDs. It becomes indistinguishable from tall tales or mythology, and while you can tell a rip-roaring good story that is both mythological and "based on some fact", there is simply no point in filling the myth with 90% of the truth, with just a few bits and pieces altered, because a person isn't meant to look at a myth as if it were factually accurate.

The universal and natural desire to be believed when you are actually telling the bare facts as you remember them militates against FLDs being an accepted practice in histories, because the readers WON'T believe what you put down that was quite factual. And this motivation cuts across all times and cultures.

Show me a way out of that problem, and I will raise my estimation of the prior probability that FDLs were an accepted practice in Hellenistic histories.

Posted by Tony | September 24, 2017 5:43 PM

Exactly, Tony. People want to know information. Christians wanted to know information about Jesus. Christopher, your apparent approach of taking it to be, I don't know, 50/50 probability or something of something *so complex* as a fictionalizing literary device is just way too high, because it runs against the grain of human nature. Punting to "it's a different culture" is just way too vague for something as sweeping as this. It's not as though it's totally *up in the air* whether the early Christians were actually *interested* in the question of what day Jesus died on or whether he really ate fish after he rose again. The overwhelming probability is that they were *very* interested in questions of that kind. After all, they created an entire new day of worship based on the day when he rose again! Why should we assume that they didn't give a flip about whether John or some other document, among the documents that were their only written primary sources for information about the life of Jesus, deliberately faked the day he died just for literary artistry or theological symbolism? Didn't care to the point where they would have said, "Oh, yeah, people make stuff up all the time in our culture, so we don't mind if John or Mark made that part up"?

Also, I really don't think you have the order of argument right. We're supposed to be *starting* with evidence *independent* of the gospels to argue that these things really existed in the culture. And to the extent that that is secular documents (which it exclusively is), you can't even get a "cumulative case" off the ground for the existence of such "devices" if a) you don't have anything like enough explicit evidence aside from examples (which we do not have) and b) the examples in secular sources can't pass the flow chart.

*Nobody*, not Licona or anybody else, is arguing from the *gospels alone* or even from the *gospels initially* that such literary devices existed. Nobody. The argument is going the other way: Oh, look, these devices existed. (On independent grounds.) Cool. Now let's see if we find them in the gospels. If the first premise fails, the whole argument fails.

So I'm afraid you can't give the whole argument a "boost" with your theological assumptions about the gospels.

Posted by Lydia | September 24, 2017 6:17 PM

We're supposed to be *starting* with evidence *independent* of the gospels to argue that these things really existed in the culture. And to the extent that that is secular documents (which it exclusively is), you can't even get a "cumulative case" off the ground for the existence of such "devices" if a) you don't have anything like enough explicit evidence aside from examples (which we do not have) and b) the examples in secular sources can't pass the flow chart.